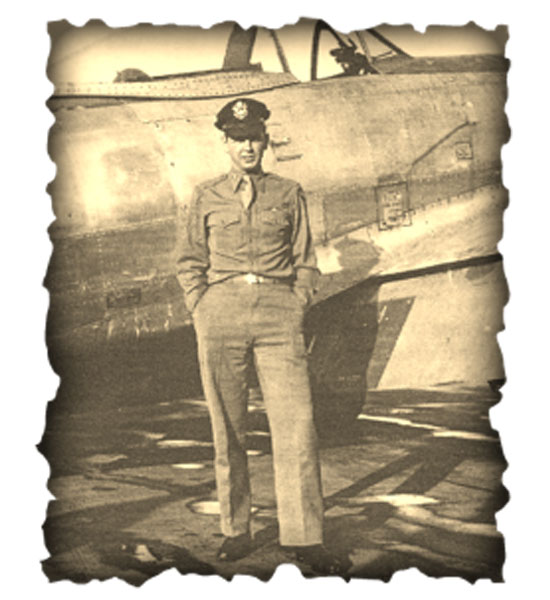

Lucky Harry

The World War II Adventures of Harry Lloyd

World War II had begun and Harry felt bad. His friends were going to war, but Harry’s job in the defense industry made him exempt from the draft. Although he had never ridden in an airplane, Harry dreamed of being a pilot. He decided to enlist in the Army Air Corps (now known as the U.S. Air Force) when he was 20 years old

Two years of college and an extensive physical exam were required in order to be considered for pilot training. Although Harry had not attended college, he passed a written equivalency exam. The physical exam was a different problem. Harry’s blood pressure was slightly over the limit. Harry explained the problem to the doctor, “I want to be a pilot so bad that when I sit here and think about it, my blood pressure goes up.” The sympathetic doctor fudged the numbers and approved Harry for pilot’s training.

Harry was excited about riding in an airplane for the first time. His instructor, who was also a civilian pilot, invited Harry into the open cockpit plane. He advised him to attach his shoulder harness and put on his helmet. The instructor flew to 10,000 feet and did loops and dives until Harry vomited, but he couldn’t dampen Harry’s enthusiasm.

Harry studied aerodynamics, flight plans, meteorology, etc., and spent five hours in a primary trainer (PT19) before making his first solo flight. He trained at 10 different air bases, earned his wings and was promoted to lieutenant in April 1944. He used his one week leave to travel back to Ohio and marry his high school sweetheart. She returned to the base with him.

Harry spent the next five months training to become a fighter pilot. He received gunnery training; practiced flying in formation, dropping bombs and dive-bombing. In September, Harry traveled for 20 days in a 100-ship convoy from Virginia to Africa, where he awaited orders.

Harry and the pilots he shipped out with were very close after training together for over a year. They didn’t know what was going to happen to them, but they weren’t nervous. The Air Corps required that potential pilots be under the age of 26. The newly trained pilots were young, brave, and very naïve.

Harry and six of his buddies were shipped to Italy as part of the “Skeeters,” the 79th Fighter Group, 87th Fighter Squadron supporting the British 8th Army. They felt fortunate to be stationed together at a base with beds and hot meals. Soldiers fighting on the ground lived in trenches and were constantly on the move while being attacked by the enemy.

The Skeeters’ job was to safeguard British troops as they pushed north, trying to reach Germany and end the war. The Skeeters were committed to bombing bridges, trains, roads, and outposts to stop the Germans and protect the soldiers.

Harry’s first mission was memorable. Captain Faison was in charge. He advised the pilots to pull up to the left after dropping their bombs because if they pulled up to the right, they would be over enemy territory and were likely to be shot. The captain knew Harry was nervous. He said, “Harry, don’t worry about anything. Just follow me and do what I do. There’s nothing to it. You’ll be my wingman.”

As the 16 planes approached the target, Capt. Faison led the way, He yelled, “Tally-ho!” then dove down, dropped bombs, pulled up to the left, and was shot. He radioed to his men, “I’m hit and bailing out!”

Harry made a split-second decision to disobey orders, which probably saved his life. He dropped his bombs, pulled up to the right rather than the left, and kept climbing. He was over enemy territory and had no idea how to get back to base. A fellow pilot flew up next to him and radioed, “Follow me!” Harry made it back to the base and was known from then on as “Lucky Harry.”

Captain Faison hid for a few days after being shot down, but was soon captured and became a prisoner of war. He was released when the war ended. Members of the squadron visited the captain soon after his release as a P.O.W. His first question to them was, “What happened to Harry?”

Harry’s luck was legendary:

- Runways were made of corrugated metal since there was no time to pour concrete. This made taking off and landing very tricky. Planes were loaded with bombs and extra gas tanks. A blown-out tire could be fatal due to resultant explosions. Harry’s plane got a blowout while traveling at 80 mph. It jumped off the runway and was destroyed by the time it stopped moving, but Lucky Harry walked away.

- If a bomb did not detach when released, the pilot had to bail out and let the airplane go. Planes that landed with unreleased bombs had blown up runways, killed pilots and stopped missions for days. People on the runway were screaming and waving their arms as Harry returned from one of his missions. Lucky Harry didn’t realize until after he had safely landed that one of his bombs was attached.

- Each pilot was allowed to name a plane, but the planes were flown by everyone. Harry prepared to take a plane on its first mission, when the pilot who had named the plane asked if he could take a picture before its first flight. This was known to be bad luck, but Harry was not superstitious. The pilot took the picture and Harry took off over the Adriatic Sea. When the engine began to sputter and miss, Harry called the tower to say he was heading back. The plane caught fire before he reached the runway. He shut off the engine and skidded along the ground. His bombs and gas tanks did not explode and Lucky Harry walked away once again.

Three of Harry’s six buddies were not so lucky:

- Morrie Loftiss from Indiana died when a “frag” fell on the runway before takeoff, and exploded. (Frags were bundles of small bombs that were dropped high up in the target area just before the squadron arrived, to make enemy gunners go into hiding.)

- Robert Malsberger from New Jersey was seriously injured when his engine caught fire and he crashed at the end of the runway. When Harry saw Robert after the war, his ears were burned off and his body was badly scarred.

- Albert Mathias from Illinois was declared “missing in action” after his plane was hit in March 1945, just two months before the war ended.

Harry and his friends were distressed at the loss of their buddies, but their intensive training enabled them to hang tough and keep going. There was no time for grief.

Harry had good times as well as bad during the war. Several rest leaves were spent in France, and one in Rome where he toured the Vatican and shook hands with the Pope. Harry received daily letters and packages from home. His mother sent canned carrot juice to help his vision. She had never worked outside the home, but took a job at a bomber plant during the war to support her son’s efforts.

Lucky Harry had 54 successful missions under his belt when the war ended in May 1945. He was shipped to Linz, Austria for occupation, where he was greeted by some of the children who had been released from concentration camps. Most were bald with bloated stomachs. Harry felt proud to know his efforts helped saved them from that hell.

Harry had been gone for 1-1/2 years when he arrived home by train in February 1946. Over the next four years, he and his wife added two daughters to the “baby boom.” Harry bought a car dealership where he became known for honesty and good service. His customers were fiercely loyal.

Harry still sees some of his war buddies at their annual fighter group reunion but says, “It’s sad when we get there and find out how many guys we lost during the year. There aren’t many of us left anymore.” But Lucky Harry keeps on keeping on.

Harry Lloyd is 86 now. He sold the car dealership and retired 5 years ago. He is a kind, fun-loving, easygoing guy who has always been extremely generous to family and friends. He remains a hero to his wife, 4 children, 15 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren. I should know. I’m Lucky Harry’s lucky daughter.

B. Jane Lloyd Published: 2007