Lloyd T. Good

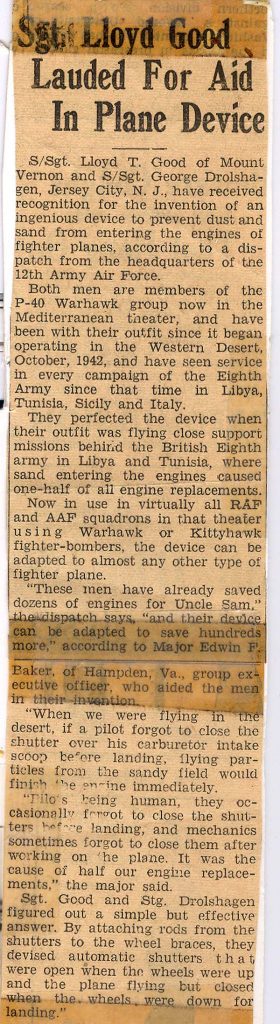

Local News Paper clippings related to Lloyd T. Good’s service in World War II

Private Lloyd Thomas Good, 20 year old son of Mr. and Mrs. Edward N. Good, graduated from the Mount Vernon High School and enlisted in the U.S. Army, January 16, 1942 at Camp Lewis. Sent to Air Corps Training School, Chanute Field, and was transferred to Curtis Training School, Buffalo, N.Y.

—————————————————————————————————————

Sgt. L. Good Wins Legion of Merit

Award of the Legion of Merit to Staff Sergeant Lloyd T. Good, son of Mr. and Mrs. Ed Good of route 3, for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding service was announced today by the war department.

With S/Sgt. George H. Drolshagen, Jersey City, N.J., Good was cited for perfecting an automatic carburetor air filter control assembly for P-40 type aircraft which helped reduce entry of foreign particles in the carburetor air intake, thus lengthening the operational life of the plane’s engines.

S/Sgt. Good, who enlisted in the service January 17, 1942, is a graduate of the Mount Vernon Union high school. He secured his training with the air force at Sheppard Field, Texas; Rantoul, Illinois, Buffalo, N.Y., and Hill’s Grove, Quonset Point, R. I., before receiving his overseas assignment October 6.

Both Drolshagen and Good are members of a P-40 Warhawk group now in the Mediterranean theater, and have seen service in every campaign of the Eighth army since October in Libya, Tunisia, Sicily and Italy.

—————————————————————————————————————

Lloyd Good in the service in the European war area, has been promoted to the rank of Technical sergeant.

—————————————————————————————————————

T/Sgt. Lloyd T. Good, Army Air Corps, who won recognition during the invasion of northern Africa for designing and perfecting in conjunction with a friend, an automatic carburetor air-filter now universally used in desert flying, is now serving in northern Italy with the Desert Air Force. The group to which he is attached is part of the most widely acclaimed air command in the world having participated in six major campaigns. Sgt. Good’s outfit has been given the Distinguished Unit Badge for conspicuous battle action, while giving close support to the British Eighth Army in the Middle East theater. Sgt. Good is the son of Mr. and Mrs. Edward N. Good of route three. He is a graduate of the local high school.

—————————————————————————————————————

S/Sgt Lloyd Good Writes of Experiences with Eighth Army – Thursday Evening, August 17, 1944

Details of the “army life” of S/Sgt. Lloyd Good, winner of the Legion of Merit for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding service, and veteran of four major campaigns in the North African and Italian theatres, have been learned here for the first time upon receipt of a recent letter by Mrs. Emma Hayton of this city.

Good, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Ed Good of route 3, sent the description in answer to a request from the American Legion. S/Sgt. Good enlisted with the U.S. army air force January 17, 1942, and was assigned to overseas duty October 6, 1942. He is a member of a P 40 Warhawk group now serving in the Mediterranean theatre with the Eighth Army.

His letter follows:

Dear Gang:

It was 21 month ago that I left the states via Newport News, and 30 months since I’ve seen the home country. We sailed out on the “Mauretania”, a British liner, and the only thing good about it is that we got here safely.

They put us up on the main deck in a room that used to be a ball room where they had built wooden bunks three high. The only reason they stopped with three was that the ceiling got in the way. As we boarded the ship they gave us tickets with the number of our bunk on it. You can just imagine the mess in that half dark room- guys with rifles, gas masks, steel helmet and hundred pound filled bags-all trying to find their places at once. I finally discovered mine after being kicked, mauled and hit on the head with every piece of field equipment issued, including shoes (with feet inside of them). By that tie I was pretty hungry, so I started out to find the mess hall, and when I did get in line, I swear that I passed through the same doorway four times. What a meal! Mutton with some sort of tomato gravy and biscuits with the tea to drink. You fellows have all heard the song, “Gee But I Want To Go Home”-well those were the kind of biscuits those were. The tea-ah yes, the tea! I’m not much of a connoisseur of tea but I know that stuff was terrible!

Anyway, we sailed south to Rio and one morning someone shouted “Land!” Everyone ran to one side of the ship and it just about tipped over, 7,000 men weighing quite a bit! The harbor was a beautiful sight though, and one of the things that I’ll never forget about it was a white statue on the top of the hill in back of the town.

We stayed there only a little while (no one was permitted to leave the ship) and then pulled out. The trip took on the same old routine as before, until one day we hit the Cape Rollers, and everyone who hadn’t been sick before, sure was then. Along with that it got colder and we had to dig out overcoats to keep from freezing to death.

We sailed into Durban, South Africa, one bright morning, and quite a few turned out to meet us. There were about 100 natives and that old faithful, “the lady in white.” I believe there was an article in Newsweek about her some time back. She sang “God Save the King” for the British and “God Bless America” for us. After throwing all of our nickels and dimes away to the natives, we stood around exchanging rumors and wondering if we would get a leave. Sure enough, the next day we were allowed ashore, and brother, we took off! Durban is a lovely place if for no other reason than that you could get eggs plain, eggs with this and eggs with that. The natives pull rickshaws around there, so four of us decided to try it. Unfortunately, Durban is quite hilly! We started down one of them. The only thing that stopped us was a luckily place telephone pole. Well after two days with nothing particularly interesting happening, we went back to the ship. We were just out from Madagascar the night it fell to the British. The flashes were visible from the ship, but at the time we didn’t know that it was the beginning of the end for that island.

We traveled up the Red Sea and landed at Port Tawfik for a six months siege with sand and more sand. After half a day’s ride on a little old train that should be in the movies, we arrived at a place called Caseferit. There weren’t any beds in the town so we slept on the cement floor in an old building of some kind. There was a German prison camp a few miles from there and I’m sure that we ate their food. One boy pulled K.P. and he hasn’t eaten rice since. We always had some kind of hard tack that we hit against the table before we ate it to just try to drive the worms out and some dishwater that the British call tea to wash it down with. It’s a darn good thing that we had just come from the states and all had iron constitutions or we would never have lived through it.

After a week in that hole we got on our little train and headed for Alexandria. The Suez Canal and the Nile Delta were the most beautiful sights in the world, it seemed, with their palm trees and green crops and that was the first time that I’d ever seen anyone carry anything on their head, and from then until now it’s been just one of those things that you see every day. It seems to me that they really need a woman suffrage law over here.

As we went past Alexandria we could see the defenses that the British had made for the protection of the city, and you can imagine how we felt, just a bunch of air corps guys who had never imagined that they would see anything like this, only in the movies.

A short time later we arrived at our field. The wind was blowing sort of hard, and if you don’t know it, in the desert that means sand. This was just an ordinary desert wind. The trucks that met our train headed in the general direction of the mess hall (some of our guys had arrived earlier to get things ready for us). Visibility was about 200 feet and we could just faintly see the men beginning to line up for chow, so grabbing our mess kits we hit the line. That was the first American food we had had since leaving the states and I’ll bet those C rations have never been appreciated that much before or since.

Back to the truck, we were shown a little hump of sand in which we were told that we’d find a British desert tent. We found it all right, dug it out, and started to put it up. What a time? The flaps would blow in the wind, it would fall down, the ropes would get tangled up. Well, after a good hour’s struggle we got the thing up, and along came the line chief and claimed the darn thing. WE put up another and found out later that it was to be used for a field marker. Between the prop wash and the landing wheels, I don’t see how the thing stood up. We had dozens of sand storms while I was there. A story of the life over here wouldn’t be quite complete if I didn’t say something about at least one of those storms.

The sand was so thick about 2 o’clock in the afternoon that I couldn’t even see the fellow in the bed across from me. I had to sleep with the blankets over my head to keep from suffocating. I tried the gas mask, but it was too hot. The next morning it was still blowing and the sand was at least two inches deep on my blankets. You guys may not believe that, but it’s the truth! I was elected to go down to the mess hall and bring back some food. I’ll bet it took me two hours to find the place for I stopped at every tent and tried to find out who lived there. I made it though and felt like I had earned the DSC or something. That storm kept on for two whole days. We received our desert training in the two months that we were there.

I spent Christmas and New Year’s in Alexandria. That’s a pretty good town, in fact one of the best I’ve been in since I arrived here. Well, the big news came late in January and 14 of us flew to Tobruk in a CD3. As we went over El Alamein we could see the fortifications that Rommel had made, but they hadn’t done him much good after all. When we got to Tobruk the town was completely demolished. We didn’t stay there long; we continued to a field 150 miles from Tripoli. The prettiest convoy I’ve ever seen was on the road to Derna on the way there. The road wound back and forth down the mountainside, and a short distance away lay the town with the blue Mediterranean in the background. The houses were white with red tile roofs and a lot of palm trees and other plants were growing along the road and by the houses. We passed through Bengasi and on to the Marble Arch, that was really beautiful with its two black statues up on the tip.

This new base was just as bad as the one at Alexandria and we’re all trying to forget it if we can. Our next move was to Tripoli and there we were stationed at Castel Benito, one of the best fields that the Italians had in Libya. The city of Tripoli was fairly nice but the Gerry thought so too by the size of the ack ack barrage that was necessary to throw up to keep him away.

When the group left, I stayed behind to help a new outfit get acquainted with our planes and I didn’t catch up with them until Kairouan and after they had gone into action on the Mareth line. We operated from there until the end of the African campaign. When the Gerries quit we had quite a time collecting souvenirs.

With my major and a couple of other fellows we went up to Tunis and fixed up a Macci 200 fighter plane. Our outfit moved to Cape Bon to bomb Pantelleria and I went along. We had plenty of work up there and our outfit accounted for five enemy aircraft. After Pantelleria we all got two months rest back at Zarzis. It was right next to the ocean and near a sulfur springs so we all got good and brown laying around in the sun.

One day we pulled out from Tripoli for a ship ride. We landed on Malta on July 4, 1943 and I think that was the swellest way to celebrate the Fourth that I’ve ever heard of. That little island sure had held out for a long time but even after all those months of bombing there were some sights to see – second tallest church dome in the world, Saint Paul’s cathedral, the catacombs and the cave where Saint Paul stayed while he was in Malta, among other things.

We left there bound for Italy on the 17th, eight days after the invasion, and landed at Syracuse. WE stayed in a staging area there for two weeks while they were marking out a field for us. After a week we moved out to the field and went back into operations. This place was a lot like the desert, the main difference was that instead of sand blowing, it was a fine dirt, but the general effect was the same.

The outfit moved up to Palagonia, the best place we have been stationed so far in the war. We could buy chickens and turkeys cheap, and grapes, peaches, peppers and onions were plentiful. We use to sit around the tent at night cooking up the darndest concoctions I’ve ever seen in my life, but they sure tasted good.

Here is where I invented the air filter for the P-40 for which ten months later Major General Carun presented me with the Legion of Merit.

During the early part of the invasion of Italy we moved to Catrone and I and another boy flew in an old Italian plane, a Savoy Machetti. We always had quite a time getting the thing off the ground but when we finally did, it was ok. When the outfit moved up the toe of Italy, seven of us stayed behind to change the motor in a plane, but after waiting seven days, and still no motor we started up after them. On the way we stayed at a nice hotel in Bari but the Germans had been there before us, unfortunately and there was no light or water system in the city; otherwise we might have been able to convince ourselves that we were staying in a hotel back in the states. WE caught up with the outfit and operated from a little old field until the ones at Foggia could be freed. We moved from Foggia to Trimoli and there we spent our second Christmas overseas.

We left the British Eighth army and their tea there, too and moved to an American outfit. I was in Naples and vicinity when Mount Vesuvius blew her top, and saw the whole thing from beginning to end.

Due to censorship this is as far as I can go, but I have tried to give you a little idea of how I won those four stars on my African campaign bar.

Sincerely,

S/Sgt.Lloyd Good

Life after the war

Your Content Goes Here

Lloyd T. Good “Sie”

Lloyd T. Good “Sie”

Sie Good was the youngest of four children born to Edward Nicholas and Mary Louisa “Celia” Good. He was born on the family farm on Fir Island in the county of Skagit, state of Washington. His parents were already old when he was born. Sie helped on the farm. They grew grains and grass and kept a small herd of milking cows, a couple of horses, a bull and a few pigs and chickens. The family home was very modest and it was hard work with little mechanical assistance. It is not known if Sie was the innovator he was to become later in his life but he did have a lot of time to think and ponder while he was pitching hay and walking behind horse drawn implements on the farm.

After graduating from high school he moved to Seattle with friends and obtained employment parking cars. He went to enlist at a recruiting office in Seattle with a cousin. Sie passed the physical, his cousin did not. His cousin went into a Sanitarium and died of tuberculosis and Sie went off to begin his military journey.

He was only 20 when he enlisted on January 16, 1942. By all accounts and photo evidence he enjoyed his military service and the men who served with him. He was a good mechanic and had a knack for seeing things from all angles. He liked making improvements and was good at it. He was awarded the Legion of Merit after devising an automatic air filter closure that operated with the landing gear to keep dust and sand out of the engine and saving the planes from crashing.

While in the military he sent many photos and letters home to his parents and siblings. His sister lived in California and made the acquaintance of a neighbor who had a younger sibling named Mary Elizabeth “Beth” Bowman. These women put their heads together and encouraged Beth to write to Sie to help keep his spirits up during the War. Beth did start a correspondence to Sie and many letters and photos passed between them. It was understood that when Sie returned stateside he would travel to Moro, Arkansas to meet Beth in person and they would determine if their relationship should continue.

When Sie was discharged from the service he returned to Fir Island and immediately went hunting (it was after all, hunting season). He finally threw his gear into an old Ford that barely ran and drove to Arkansas to claim Beth.

They decided that the match would be a good one and married a few days after meeting in person. They married on Beth’s 20th birthday, December 11, 1945.

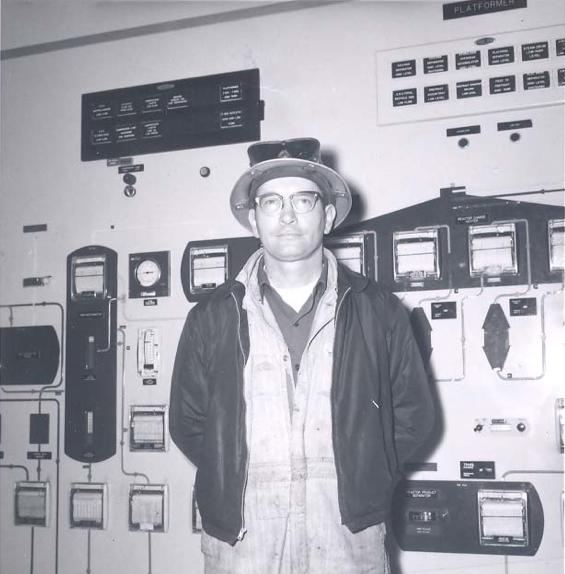

They proceeded to drive home together and nearly froze to death but Sie kept the car going.When Sie and Beth returned to Fir Island they set up housekeeping in a small cabin situated on top of a levy near the family farm on Dry Slough Road. They lived in this tiny abode for nearly a dozen years while Sie farmed with his father and Beth cared for their 3 children and her aging in-laws. In 1958 Sie and Beth bought the 60 acre home place from his parents and started making the switch from dairy to crop farming. About this time Sie became employed by the Shell Oil Company in Anacortes and worked as labor to build the new refinery.

This new income stream allowed him to expand his acreage and upgrade his equipment little by little. Sie juggled farming, shift work and the building of a new and more spacious home to house his growing family. They had 4 children by the time they moved in.

This new income stream allowed him to expand his acreage and upgrade his equipment little by little. Sie juggled farming, shift work and the building of a new and more spacious home to house his growing family. They had 4 children by the time they moved in.

Sie was hired on as an operator at the Shell Refinery in Anacortes, Washington and stayed for the next 25 years, retiring in 1980. He continued to innovate at work, creating numerous labor saving devices. He was 59 at retirement having earned his 80 points and he promptly turned in his lunch pail, and climbed on his son Steve’s fishing vessel and headed for Alaska for the summer to observe the commercial fishing industry first hand. He studied the process and came home inspired to improve the methods of hauling fish onboard. He made several trips to Alaska to fish and mingle with the crews. He did not stay for the whole season.

He was still farming at this time and as summer is the busy time for farmers, the weeding and harvesting was left to his son-in-law, Mike and daughter Laurie, who live on the property. Beth was also left behind to tend the home and the farm chores. This was not a popular decision.

By 1987, Sie was ready to retire from farming. He leased the farm, equipment included, to daughter Laurie and her husband Mike. Sie had other things to do but he kept a close eye on the farm operation.

By 1987, Sie was ready to retire from farming. He leased the farm, equipment included, to daughter Laurie and her husband Mike. Sie had other things to do but he kept a close eye on the farm operation.

Eventually he found some trust and decided to leave the farming to the youngsters. Now he could focus on travel. For many years Beth had made a solo trip by airline to Arkansas to visit her family. Sie’s job at Shell kept him from accompanying her. Now he was free to go along but he wanted to see more of the country than just Arkansas. So he and Beth bought a small motor home and began to leave Fir Island every fall for a month long trip across the states to spend time with Beth’s family in the Southern states. On one of their trips they picked up a stray dog, at a rest stop and brought him home with them. Sam became Sie’s devoted companion for many years.

They made one trip across the country to Maine in their motor home to visit daughter, Susan and her family but abruptly returned when their home on Fir Island was robbed in their absence. Eventually they bought a bigger, more comfortable and spacious rig and used it for many years to drive through the states, marveling at changes in landscape, stopping at all the historical sites and spending a few weeks with Beth’s people. There was always a list of things that needed fixing for Sie. He loved to help and they loved to keep him busy.

They made one trip across the country to Maine in their motor home to visit daughter, Susan and her family but abruptly returned when their home on Fir Island was robbed in their absence. Eventually they bought a bigger, more comfortable and spacious rig and used it for many years to drive through the states, marveling at changes in landscape, stopping at all the historical sites and spending a few weeks with Beth’s people. There was always a list of things that needed fixing for Sie. He loved to help and they loved to keep him busy.

November 11, 1990, Sie and Beth were visiting in Arkansas when the rain fell for days back home. The levy protecting Fir Island gave way and the ensuing flood destroyed the contents of their basement and damaged equipment stored in sheds on the property.

The repaired levy failed two weeks later on Thanksgiving Day and Fir Island flooded again. Sie and Beth were back at home parked in their front yard in their motor home waiting it out. Undaunted, Sie took his video camera and borrowed a small boat and motored around the flooded island, recording the damage. When the levy’s failed in 1953 the farm was flooded and Sie was a young man. He rowed across the land in a row boat and tended his cattle. It was a lot harder to manage the repairs in 1990 but he got everything up and running again and they were able to move from the motor home into the house.

After things dried out Sie had truckloads of fill brought in and built a new shop next to his house above flood level. He installed an elevator so he could haul things high enough to keep them dry in the event of another high water event.

After things dried out Sie had truckloads of fill brought in and built a new shop next to his house above flood level. He installed an elevator so he could haul things high enough to keep them dry in the event of another high water event.

For a few years hunting in Canada for the elusive moose became an annual event in Sie’s retired life. His cousin, Pat Good, organized several well appointed trips and Sie eagerly joined the group. He steadfastly remained the only hunter to stalk his prey on foot, refusing to be guided to the animals. His children and Beth were relieved when he gave up the trips as Moose meat was not a favorite.

Sie loved reunions. He had many cousins and always went to their reunions. He attended his high school reunion and made it back to at least one reunion of his fighter group. He and Rocco Soranno reconnected in their senior years and Rocky visited Sie on Fir Island twice. Sie was a proud member of the Pioneer Association of Skagit County and went to their picnics each year.

His farm was part of the original homestead of his grandfather, Edward Eady Good and Sie was always proud that it had been kept in the family while other parts of the homestead were sold off.

His farm was part of the original homestead of his grandfather, Edward Eady Good and Sie was always proud that it had been kept in the family while other parts of the homestead were sold off.

As an airplane mechanic, Sie loved planes. He owned three aircraft in his lifetime. The first, a Piper J5, a beautiful little red three seater that he flew for several years on his student permit! He acquired the J5 for $800 and his Triumph motorcycle. He was glad to rid himself of the motorcycle. While riding the bike in Seattle he was hit by a car and broke his arm. He never regained full extension of his elbow. Better to own an airplane.

He was lucky that a local man, Frank Barker, had a flying school and airstrip less than 3 miles away from Sie’s farm. Frank Barker was a former barnstormer so he was much admired by aspiring pilots.

Sie flew the J5 as if he was a barnstormer! Thrilling his son but terrifying his friends. He maintained a runway on the farm and put up a windsock and took to the skies with his little dog Peanuts as passenger most trips. Undaunted when the family horse, Chico, chewed holes in the covers of the wings of the J5, Beth made new covers and Sie patiently coated them with 5 coats of butyrate aircraft finish and 5 coats of opaque aluminum. He finished with 3 coats of color to make a drum-tight skin.

While on a joyride in the J5 near Eatonville, Washington with his son, Steve, he spotted the fuselage of a plane in a cow pasture and dipped lower for a closer look.

While on a joyride in the J5 near Eatonville, Washington with his son, Steve, he spotted the fuselage of a plane in a cow pasture and dipped lower for a closer look.

Sie immediately knew he had spotted a treasure. He landed the J5 and engaged the owner in conversation. No one recalls what he paid to close the deal but Sie drove down and picked up all the parts to construct a Meyers OTW-145, N34301, Serial #45. Certificate of airworthiness Date: 1941. He brought the whole lot home and stored everything in his granary, safe and under cover. He always hoped to restore the Meyers himself but he never found the time. He met airline mechanic Ralph Prissel, in Concrete, Washington while attending an air show. Ralph used to work at the Meyers Factory.

They struck a deal.

Sie trucked the fuselage and the wings up to Concrete and Ralph rebuilt and covered the wings with a bright, buttery yellow skin and removed the paint from the fuselage. At this point, Sie brought the unfinished bird home and tucked it back into the granary. He had hoped to donate the Meyers to the Boeing museum but they would not accept a plane that was not fully assembled. The Meyers stayed in the granary and Sie fended off offers from local pilots for a few years. In 1997 he turned it over to Air Care International, Inc. in Goleta, California for a tax deduction. The Meyers OTW-145 is now in the UK and owned by a private individual. It is not flying yet. Sie’s third and final aircraft was an Ultra light. He bought it in 1984 as a lark and only flew it a few times. He welded up a special cart/trailer so he could maneuver it into his shop. After crash landing on his airstrip at home he decided to abandon the Ultra light for safer modes of travel.

His son-in-law, Mike Olds, took lessons and became certified and he flew it for a few years before parking it back in the shop where it resides today. Though he wasn’t flying planes, Sie took in air shows regularly and visited the Boeing museum of flight on many occasions. His grandson, Jeffrey Olds, is a mechanical engineer working on aircraft for Boeing and Sie would be so proud to know that.

His son-in-law, Mike Olds, took lessons and became certified and he flew it for a few years before parking it back in the shop where it resides today. Though he wasn’t flying planes, Sie took in air shows regularly and visited the Boeing museum of flight on many occasions. His grandson, Jeffrey Olds, is a mechanical engineer working on aircraft for Boeing and Sie would be so proud to know that.

Sie was always busy. He instilled a strong work ethic in his children, inspiring them to do their best work and to look at things from all sides. Beth was equally busy. She supported Sie in all of his endeavors and kept things humming along while he was working or off on his adventures.

Sie and Beth remained lifelong partners, married for 61 years. They worked hard, pulling together to get through some very tough times. They had high school educations but were lifelong learners, innovators and (Beth especially) very creative. Sie never stopped being amazed at new gadgets and would throw himself into learning new technologies. He read the Wall Street Journal daily and became interested in investments in the 1960’s. He made modest gains until the early 70’s when he got serious about the stock market and then his portfolio became very comfortable.

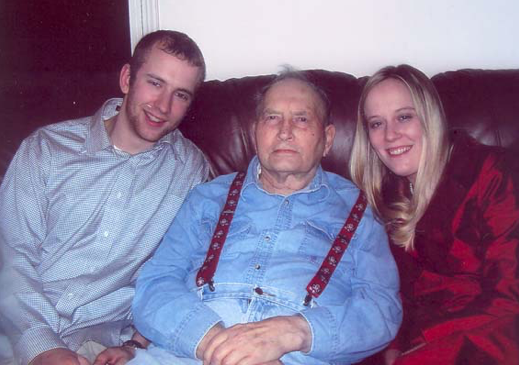

Sie and Beth had four children and seven grandchildren. Two of their grandchildren, Kelsey and Jeffrey Olds grew up on the Family Farm and spent their young lives interacting with Sie and Beth.

Sie and Beth gave generously to all their grandchildren so they might have college educations. As children of the depression era they were frugal and cautious about spending money. Their thrift allowed them to remain at home with help when their health began to fail.

Beth passed away first in 2006. Sie remained home for another 9 months with help in the house and family next door to oversee his care.

Beth passed away first in 2006. Sie remained home for another 9 months with help in the house and family next door to oversee his care.

He was comfortable and content to be in the home that he had built with his own two hands on the land that had been in his family since the late 1800’s. Lloyd T. Good died on in the early hours of September 11, 2007. He was just a few days shy of his 87th birthday.

Sie was laid to rest in the family plot at Pleasant Ridge. His daughters commissioned a custom urn for Sie from a local artist and welder. The top features a light bulb which signifies all of Sie’s great ideas. The inscription reads “Sie Good – One Heck Of An Ingenious Guy – September 15, 1921 – September 11, 2008.

Every time dad was about to take a trip he laced up his boots, zipped up his old coat and pulled on a cap. He took his dog and they walked every inch of the farm, taking it in, enjoying sights and smells of home before it was time to leave.

Additional Photos

Sie returned from the war to work with his father on the family farm. This was the grain harvest.

Lloyd T. Good wearing his World War II Veterans cap at his last family reunion June 2007.