Richard F. Hobbs

The written recollections and letters of Operations Clerk Richard F. Hobbs, from the Hobbs family

WRITTEN RECOLLECTIONS OF RICHARD F. HOBBS, Jr.

WORLD WAR II

Edited by Michael E. Hobbs

As far as I am concerned, World War II began in the spring of 1941, when I was a student at North Georgia College. Major Green, who was a professor of military science and tactics, told us to get ready. We would soon be back at war in Europe.

Then came December 7, 1941 (Pearl Harbor Day). I was living in Milledgeville, Georgia with my parents. I had worked for a local newspaper and that morning I was called in to help get out an extra edition. That day, I told the owner of the paper I would be joining the service.

On December 15, I went to Macon, Georgia to the recruiting station where I took a physical exam. Thereafter I was taken to Fort Benning on a bus with other recruits. For the next three days, I attended classes on military history, discipline, etc. There were so many joining the Army at that time that it was December 19 before I could be sworn into the service. I had always wanted to fly, so I asked to be assigned to the Army Air Corps. I was sent to Keesler Field near Biloxi, Mississippi for boot training.

Boot training was easy for me since I knew the drill and was used to the military discipline. I was put in a flight with about 200 other men. I was checked mentally, physically and morally. After a few days, I was placed on KP (kitchen police) on the night shift. The mess hall served 1600 men on each side, 3200 men at each sitting. I was put on the egg detail. All night long, I cracked eggs. I never knew there were so many eggs in the world. I got to the point where I could crack four eggs at one time! I did not know that this would be the only time that I would pull KP.

We went to many lectures about military life, etc. One of the things we had to do was list all of the schooling and experience we had in civilian life. I had two years of college, two years of ROTC, had worked for a newspaper, one summer driving a gas truck, one summer driving a tractor and skidder with a logging crew, and I had worked in my father’s drug store. I had also worked in a grocery store.

I listed my hobbies as sports and photography.

After about two weeks, I was called into the CO’s office. He had read my résumé and found that I had some military training. He asked if I would become platoon sergeant for the rest of the training period. I accepted because at this time they did not have enough cadre to train all the men entering the service. The CO told a sergeant to take me to the barracks and put me in one of the non-com’s rooms. No more KP for me! All I had to do was call the roll and march the platoon to the mess hall and to meetings.

They tested us for everything and we were told to decide which school we would like to go to. I asked for Air Gunnery. When the order came out, everybody was ordered to schools except eight of us who made the best scores on the tests.

We were ordered to the 20th Pursuit Group at Hamilton Field in California. We traveled on a troop train and went from Mississippi through Alabama and Georgia to Chicago, then south to Texas, New Mexico and then on into southern California. Hamilton Field sits on Oakland Bay. Ultimately, I was assigned to Headquarters Operations. The 20th Pursuit Group was the second oldest outfit in the Army Air Force. Most of the men had been in the group for many years.

You must realize that the war was just beginning and the Army was afraid that Japan might try to invade the west coast. I was ordered to stay in Operations 24 hours a day. Food was brought to us there. We had one rifle and two clips of cartridges for the two of us. I don’t know how we were to stop anything!

Next door to Operations office was the Link Trainer section. I made friends with the operators who also stayed in the hanger at night. I told them that I wanted to fly and was trying to get in the Flying Cadets. Since we had nothing to do all night, they agreed to teach me to fly. I learned to fly on the instrument but had not been off the ground in my life.

The pay was $21.00 per month but after about three months, I was made PFC and the pay schedule went up also.

I was now making $36.00 a month.

Soon after I got to Hamilton Field, the Air Corps, knowing they would need many pilots, reduced the age and the schooling necessary for flight school. Under the age of 21, you needed your parent’s permission. My parents gave their permission knowing how much I wanted to fly. I took the physical for flight school and found out that I was color blind and would not be permitted to fly. This was probably the worst day of my life.

After a few weeks, we were given 12 hour leaves. I went into San Francisco a few times, but I didn’t get to see much of the city.

In March, 1942, we were ordered to the east coast. This time the troop train took the northern route. It took us through Wyoming. In the mountains, we just about froze since the heaters in the train cars had frozen up. We lived on peanut butter sandwiches and lemon juice for several days. Somewhere in South Dakota we were allowed off the train for a little while. As luck would have it, there was a beer place right there. We filled the toilet with beer and packed it with snow. The rest of the train ride, all the way to Wilmington, NC, was uneventful.

The afternoon we came into Wilmington, several of us were assigned to guard the train and all of our equipment. Dark came, but no relief came. No food came. It was the coldest night that I have ever endured. So, sometime during the night I climbed into one of the big trucks, started the engine and turned the heater on. It felt just great! Half of us would stay in the truck and warm up while the rest of us stood guard. Daylight came, but still no relief. We were cold, tired, and hungry— and teed off. There was a little café that we could see, so we decided that one of us could go down and see about getting us some food. We were not supposed to leave our post, but one of us did and the food was great, as I remember. Sometime later that afternoon, we were finally relieved with an apology. We had just been forgotten.

We spent a short time at the air base in Wilmington, but soon we were sent to Myrtle Beach. We were the first outfit to go there. It was just a runway, a water spigot and a swamp, but it was not bad. The people at Myrtle Beach were great. Some of the soldiers were married and the people who owned cottages on the beach let them stay there rent free. There was a USO building there, too, and the ladies did many nice things to help us. I got to fly in the nose compartment of an A-20 and we buzzed the beach.

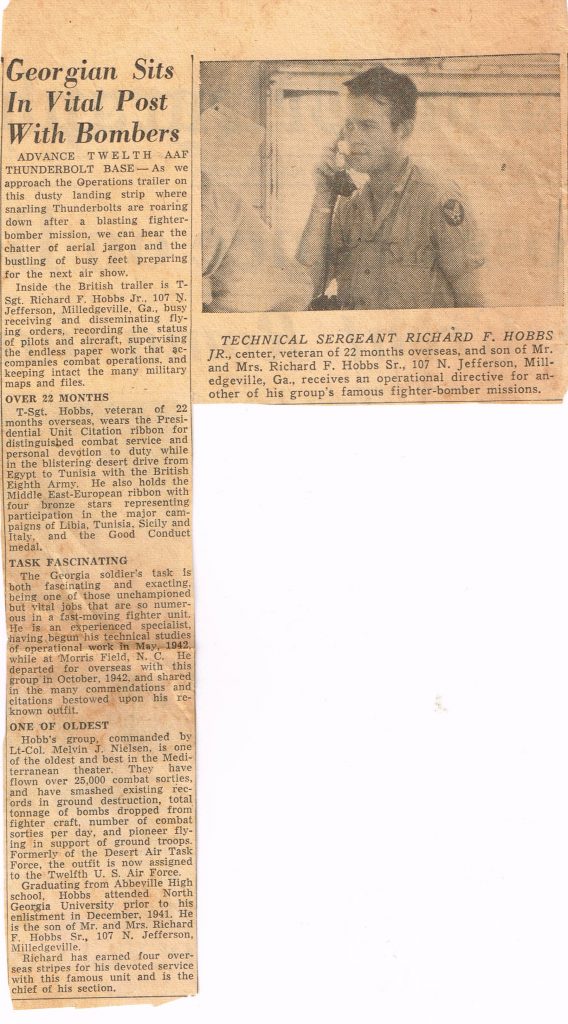

From Myrtle Beach, we went to Morris Field at Charlotte, NC. The 20th Pursuit Group was to be a cadre outfit to train troops and pilots for overseas duty. I found out that a new outfit was being formed and I signed up for it. When the orders came down, I was transferred to a motor vehicle outfit. I went to the base headquarters and complained. I was told that the assignment would be corrected, but that I would have to work in the motor vehicle unit for about a month until the new orders could be cut. The motor vehicle outfit was new. It had a lieutenant and forty men, all of whom had just finished boot training. The lieutenant asked me if I would be acting first sergeant for the unit since I had been in the service longer than the rest of his men. When the orders came out the following month, I was assigned to the 79th Fighter Group and was assigned to Group Headquarters in the Operations Department. I recall that as we were just getting organized, there was a lot of confusion during this time.

After we were transferred to Bedford, Massachusetts, the Group really began to take shape. We were headquartered in a big red barn. Our commanding officer was Col. Peter McGoldrick.

One day, an older first lieutenant came into the Operations Office. He said his name was McEwen and the first thing he said was that he was lost. He had been a pilot during the World War I, but did not see action overseas. He was commissioned straight from civilian life. We got to be on friendly terms. He told me that if I could look out for him, he would always back me up. He turned out to be a good and effective officer.

Soon after we got to Bedford, Kenneth Handley and I were instructed to report to the CO’s office. Col. McGoldrick told us that we were the only two men in the Operations section that he wanted to take overseas. We were instructed to take a test which would determine which of us would be the Operations Chief. I had been reading the Army and Air Force regulations while I had nothing to do and I guess that made the difference. Anyway, I came out on top. Then, the colonel told us that we would be promoted to buck sergeants. PFC to buck sergeant! $72.00 per month!

We were rich!

In September, 1942, when Handley and I were paid, we went into Boston to celebrate. We went to a big hotel on the commons and ordered the largest steak on the menu. When we asked for the check, the waiter told us that it had been taken care of by another diner. He would not tell us who had paid our check. All that money, and we couldn’t spend it!

Later that month, I was given ten days leave to go home. But after I was in Milledgeville for only three days, I received a telephone call from Lt. McEwen to return immediately to the Boston Information Center. I knew that meant that the 79th had received orders to go overseas. When I returned to duty, we packed up all our equipment and after about a week, we were put on a train and sent to Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania. There, we were given all sorts of shots and more physical exams. From there, we went to Hampton Roads, Virginia near Norfolk. We boarded the Mauretania, which was formerly a Cunard luxury liner. I was birthed on the main deck, aft. All the windows and portholes were boarded up. We slept in hammocks over the tables where we ate our meals. We had two meals a day. It was English food. It was terrible!

We left Hampton Roads on October 9, 1942. We were alone! The ship did receive air cover for several days, but then we were entirely on our own. The ship zigged and zagged every fifteen minutes to avoid U-boat torpedoes. We went through the Caribbean, which at the time was a hot spot for German U-boat activity.

At North Georgia College, I took a course where we were required to map the stars. I met another guy who knew the stars and we worked together to try to figure out our positions at sea. We were good enough to figure out that we were headed to Rio de Janeiro. At the time, Rio was an open port. We were circled by a Brazilian ship while we took on water, etc.

From what I could see from the deck of the Mauretania, Rio was a beautiful place.

On October 20, we set sail again. We ran into cold and stormy weather and a U-boat scare. Going around the Cape of Good Hope, we were freezing whenever we went out on deck. We put into Durban and were given two days shore leave there. The first thing we did was to find food. I found a steak house and made a pig of myself. The people of Durban were very friendly and I liked them very much.

On November 1, 1942, we sailed out of Durban, escorted by two destroyers. As we left, shore batteries fired at a U-boat and the destroyers dropped depth charges. When we entered the Indian Ocean, we found the water to be smooth as silk. We sailed up the Madagascar Strait and could hear the big guns firing in the last battle of Madagascar. We sailed up the east coast of Africa and into the Red Sea. We entered the Port of Tewfik at the southern end of the Suez Canal. We had been at sea 37 days.

We were sent to a transit camp for the British 8th Army and found out that things on the ship weren’t so bad after all. The food there was uncooked and covered with flies. We slept on the ground. After a night train ride in an open car on a narrow gauge railroad, we arrived at Amira where we loaded into British trucks and were carried to Landing Ground 174.

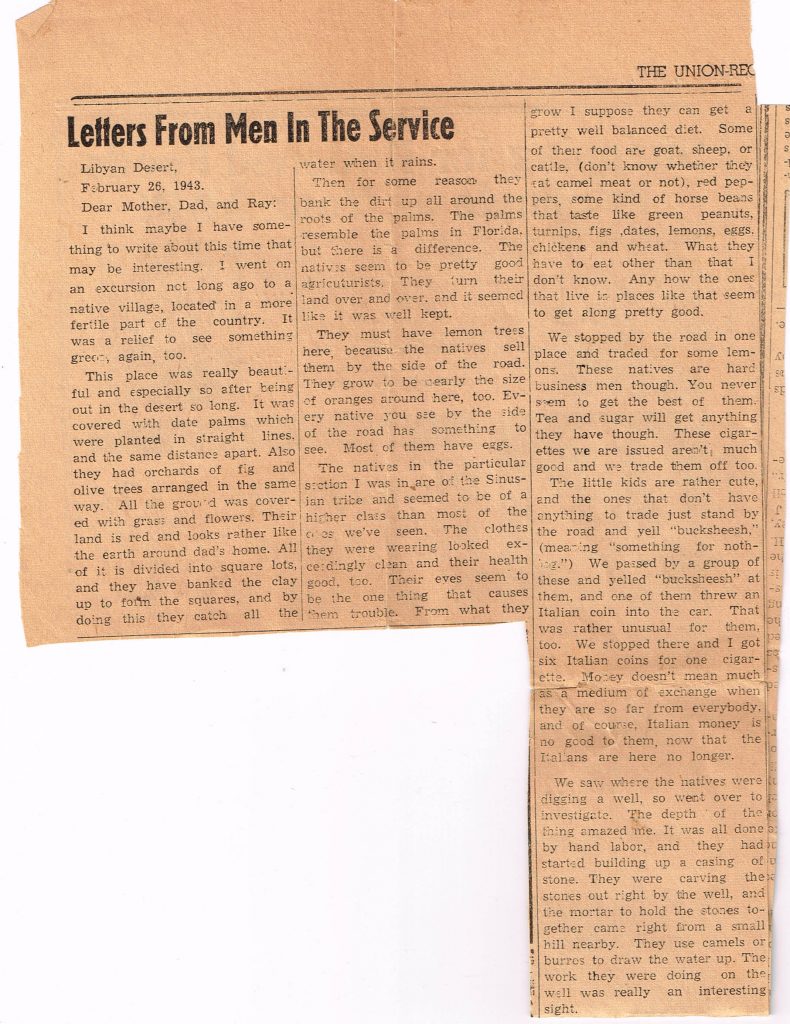

The Battle of El Alamein was still going on, so we were really just in the way of things. We learned by trial and error. We had British tropical tents and we quickly learned to tie them down securely because we had our first dust storm almost as soon as we arrived. Two days and three nights the wind blew and dust covered everything. All we could do was lie on our bunks with our heads covered with blankets. We had 12 sand storms while we were at LG 174. We learned to keep water, food, dust respirators and goggles in our tents.

After the first dust storm, our heaters would not work. Our first meal was cold pork and beans covered with flies and sand, but it was one of the most memorable, if not best, meals I ever enjoyed.

The 79th Fighter Group was part of the 9th Airforce, but we were attached to the British 8th Army. Little by little, our pilots and planes were coming in to the LG. The 9th Air Force required daily reports but we had no communications net at that time, so it was my duty every night to take our reports to a British communications outfit about eight miles away from our LG. I carried the reports in a small right hand drive Dodge truck that was only outfitted with black- out lights. I did okay when the moon was shining, but when it wasn’t, I had trouble. We only had some tracks to follow to the communications unit and it was not unusual for the wind to cover the tracks with sand. I got lost several times.

I never saw any snakes, but there were plenty of scorpions. We soon learned to shake out our blankets and boots before using them. The flies were terrible and there were frequent bouts of diarrhea. Our tents were separated bout fifty yards apart to make it difficult for the enemy’s bombs and strafing to hit us. We all dug slit trenches in front of our tents to have something to jump into in the event of a German air raid.

During this time, Col. McGoldrick was killed while flying missions with the 57th Fighter Group. Col. Bates took over as commanding officer.

We were allowed to go into Alexandria, which was about thirty miles away. We had some trouble with a few of the British troops we ran into, many of whom were AWOL from the 8th Army. We soon learned to stay together in groups as we traveled around the town.

We spent our first Christmas overseas at LG 174. Mail was finally beginning to arrive. The Unit was beginning to take shape, but we had a long way to go. We had a Christmas party. We put grain alcohol in a big tub and filled it with powdered grape fruit juice and water.

It was a real bash!

All of us had to pull guard duty. Sometimes I was just on guard duty, and sometimes I was Sergeant of the Guard. The time that I remember most, I was on guard duty on one of those dark nights. There was no horizon and sometime out there in the dark you see things that are not there. I thought I saw a shape and thought that it began to move. I thought it, in fact, had begun to circle around me. I didn’t want to be an idiot about it since one of our troops on guard duty had killed a donkey a few nights before. He, too, had seen something move, and when he got no reply to his challenge, he fired away. When it was all over, we found that he had killed a little donkey the natives were using. From that point on, the soldier was known as “Kill Ass.”

Finally, I approached the shape with my Tommy gun on ready and found out that it was just another oil drum. I have to admit that I was a bit afraid out there, but I leaned what your mind can do under those circumstances. I did not tell anyone about this for a long time, but when I did, I found out that other people had had similar experiences. I never got over the fear I had, but I controlled it.

On January 27, we started out across the desert toward Tunis. It was about a 1500 mile trip. We passed El Daba, Marsa Matruh and Tobruk and stopped at LG 150 near Gazala. We arrived in another sand storm, so it was a couple of days before we could see what we were into. There were mine fields all around us. This was the most forlorn part of the desert that we would ever see.

Somewhere between Tripoli and Tobruk we experienced our first combat. We were the subject of an air raid by German Stukas. All across North Africa, there was only one paved road that followed the coast line. It was always full of traffic. Our trucks were mixed in with the British convoys when we were hit. We knew to get the vehicles off the road and run away from them. I saw the British boys shooting at the Stukas so I did the same. I had only one clip, so it didn’t take me long to run out of ammunition. I didn’t see any damage to our vehicles,

but the Germans scared us pretty good.

Tripoli fell and we went to Castel Benito Air Field. It had been Mussolini’s pride and joy. When we got there, it was just a pile of junk. But the guys thought that Tripoli was heaven. After going all this time without any alcoholic beverages, there was wine in Tripoli. All the empty Jerry Cans were filled with wine. Things weren’t too bad for a while.

From Castel Benito we moved to Zuara for a short stay. Then we moved to the Causeway LG, which was a sand spit jutting out into the Bay of Bou Grara not far from the island of Djerba. Here our combat operations really started increasing and a lot of things began happening. One of the first things was the loss of Captain Boggs, our Operations Officer. He was a first class man.

The Germans really wanted to get us. Night after night they would come into the area and drop flares trying to find our unit. One day we were alerted to an air raid, but the Spitfires hit the Stukas and ME 109’s before they could get to our field. I watched through my field glasses as several planes went down that day. We learned that it was a Polish squadron who saved us that day.

One night, we had an A-20 crash close to our tent area and it had been loaded with bombs. Col. Bates told me to get some men and police the area and see if we could find any papers, maps, etc. In the crater, we found one man’s arm with a wrist watch attached. The watch was engraved on the back. This was all we were able to find. We buried it in a grave which we marked with the names of the six airmen in the crew. I was in charge of the gun salute when we buried the remains. I believe this was the first of two such formations I attended while overseas. We flew the watch back to the A-20 outfit.

We were told by the British that there was a report of German paratroopers being dropped in our area. We were ordered to sweep the whole area to see if we could find them. Col. Bates told me to get some men together and check the little town of Zarzis. We did a house to house search on maybe 20 houses. We found no Germans, but we did find a truck load of materiel that had been stolen from us. I was surprised at the houses that I entered. All had a hand cranked Singer sewing machine. The back of the houses was where they kept their chickens, donkeys, etc., but the front of the houses had no odors.

We flew missions as fast as we could. That meant that I really had to work! Col. Bates used me for several different jobs. Sergeant Moore and I were assigned to investigate all aircraft accidents and follow up on any aircraft that had been shot down.

We were in combat all the time now, and lost a number of pilots. One of the things Operations had to do was file the Missing Aircrew and Killed in Action reports. It was form 13 and I felt funny using a Form 13 for that purpose. Col. Bates had me write letters to the next of kin. We usually sent a map where the pilots were last seen and a description of what had happened. I had a hard time writing those letters.

As the front moved away from us, we had to move. Our next LG was La Fauconnerie Air Drome. On our way there, the convoy had stopped so everyone could stretch their legs. We noticed a cloud of dust coming up behind us. Finally, we could make out a line of tanks coming our way. The tanks belonged to a British unit and when the lead tank pulled up, an officer asked us what we were doing there. When we told him that we were on our way to La Fauconnerie, he told us that the Germans still had the field. He said that he didn’t think that General Montgomery wanted his air force to get out in front of his tanks. Major Snowdon decided to follow the tanks and see if the information was correct. When we got there, the Germans had just pulled out and left fires burning and booby traps everywhere. We operated from there for only three days before we had to move again.

On April 18, 1943, we moved to Hani LG, just outside of the town of Kairouan, a Muslim holy city. This was a flat, hot, bug infested area. The war was winding down in North Africa, but we were flying missions as fast as we could. But when I had some down time, I made a visit to Kairouan and obtained a permit to enter the very large mosque there.

After the Germans pulled out of North Africa, we had a field day. Everybody had a vehicle. I had a Fiat car and a motorcycle. We had piles of German and Italian weapons and ammunition. We went into Tunis and saw pretty French girls. Several of us took a motorcycle trip to Bizarti to meet some of the American GIs that had come across North Africa from the west. Three of us went to Carthage. We also had a visit from Captain Eddie Rickenbacker. He stayed in the Operations unit a lot of the time he was with us because that was “where the action was.” He was quite a man.

The “A Party” was moved to El Houaria LG on Cape Bon to fly missions in the assault on Pantelleria and Lampedusa. After the islands were taken, we had plenty of time on our hands. We rode motorcycles, drove our cars around, and took target practice with all the arms and ammo the Germans had left behind. We would line up German helmets and hold rifle practice every afternoon. There was a tall bluff on the north side of the cape overlooking the sea and we would go up there to shoot at the birds flying down below us. We found two large guns and ammo up there on the bluff, but we didn’t think they were usable. We had a pilot, a captain, in the group that had been in the artillery, so we took him up on the bluff to take a look at the guns. We worked on one of the guns for a while until we figured out how to operate it. The captain told us to take cover and he would fire it off. When it fired, all of us ran up to the edge of the bluff to see the shell splash. We didn’t know there was a convoy of allied ships going by. We thought we were in big trouble, but nothing ever came of it.

About the middle of June of 1943, both “A Party” and “B Party” returned to the Causeway LG for invasion training and to get our vehicles fixed up so they could go onto the beach from an LSV without drowning out. At this time, I had little to do, so three of us got permission to go across the strait to Djerba. We hired an Arab boatman to take us to the island and we got on a bus to take us to the town on the north end of the island. The bus was an open air affair and looked like it was left over from World War I. By the time we got loaded, we had chickens, goats, natives and I don’t know what else hanging all over the top, sides and rear of the bus. We got good seats since I was the only one with a Tommy gun. After about a mile or two, we were stopped by a gendarme who put several men off the bus. I guessed that there was a limit on the number of passengers the bus could carry. All the men that were taken off the bus went down the road while the driver argued with the gendarme. Anyway, we picked them back up around the next curve in the road. This happened about three times before we reached our destination.

Our first night on Djerba was a bad one. We went to a small hotel and as soon as we laid down to sleep, the bed bugs started chewing on us. I finally sat in a wooden chair most of the night. Daylight found us on the beach. We went in the water with all our clothes on. We found another place to stay the next night.

There were lots of French people on the island, but mostly Arabs. We found a place to sleep and then started to explore. We went to a temple where we were required to take our boots off. There were lots of tapestries and gold and silver goblets in the temple. To this day, I am not sure what religion was practiced there. There was a large fort on the north side, too. It was made so that any rain that fell funneled into a cistern. It was made of stone blocks.

When it was time for us to leave Djerba, we found that Friday was a holy day and that no buses ran. We had to be back at the dock at a special time to meet our boatman who would take us back to the mainland. There was no other way to get there except to walk, which is what we did—18 miles. But sure enough, when we arrived at the dock, our boatman was there waiting for us.

Not having much to do at this time, several of us did a lot of riding on our motorcycles on the rough terrain around the LG. After several days of this, I began to experience some pain at the base of my spine, so I went to see the flight surgeon to see if he could fix it. He rolled me over a hot oil drum and called a couple of the medics over. He told them that at the base of my spine was what is known as a pilonidal cyst and that he was going to send me to a field hospital to have it removed. I spent three days at the field hospital without anyone ever looking at me. It was hot and the flies were awful. I found a nurse and asked her what they were going to do with me. She said that the plan was to operate to remove the cyst and that I could expect to be in the hospital for about two months. I didn’t like the sound of that at all. That night, two of the medics from the 79th came by. I found an old pair of overalls and went back to the unit with them. The next morning, I asked Sergeant Lynch to put me on the morning report as present, knowing that otherwise I would be considered AWOL.

Three days later, I was on a plane bound for Malta and the “A Party.” On Malta, we slept on the ground,

but we had a very nice place to go swimming.

On July 16, we left Malta for Sicily. We landed between Augusta and Siracusa on the east coast. While we were waiting for our air field to be prepared for service, we sweated out nightly air raids, but we filled our stomachs with melons, fruit, tomatoes and wine. Many of us had sores that we called the Egyptian crud. I believe it was the beginning stages of scurvy, but with the good food we had available in Sicily,

it all cleared up within ten days.

On July 26, we moved to our air field at Cassibile LG and landed our planes there. The next day, we flew our first missions from Sicily. The “B Party” came to us on the 28th after five weeks being apart. The next morning, we were strafed by two ME-109s but we only lost one air plane. On July 31, we moved to Palagonia LG near Catania, not far from Mount Etna. From there we flew missions mostly around the Straits of Messina as the Germans were pulling out of Sicily.

On September 13, 1943, the 79th crossed the Straits of Messina to Italy, initially setting up shop at the Crotone LG. If my memory is correct, the 79th was the first allied fighter group to operate from Italian soil. We moved several times after relatively short stays. First we went to Firma LG then to Pisicci LG for a few days, and then to Penny Post. Penny Post was heavily mined and a group of British sappers were killed when they were blowing up the mines. Next we went north to Foggia No. 3 Air Field. Col. Grogan, who had been the group operations officer while at the same time serving as a pilot, left the 79th for the U.S. He was another great officer. He told me to do what was necessary in Operations and that he would see that I was covered. I answered his phone calls and signed his name to routine orders.

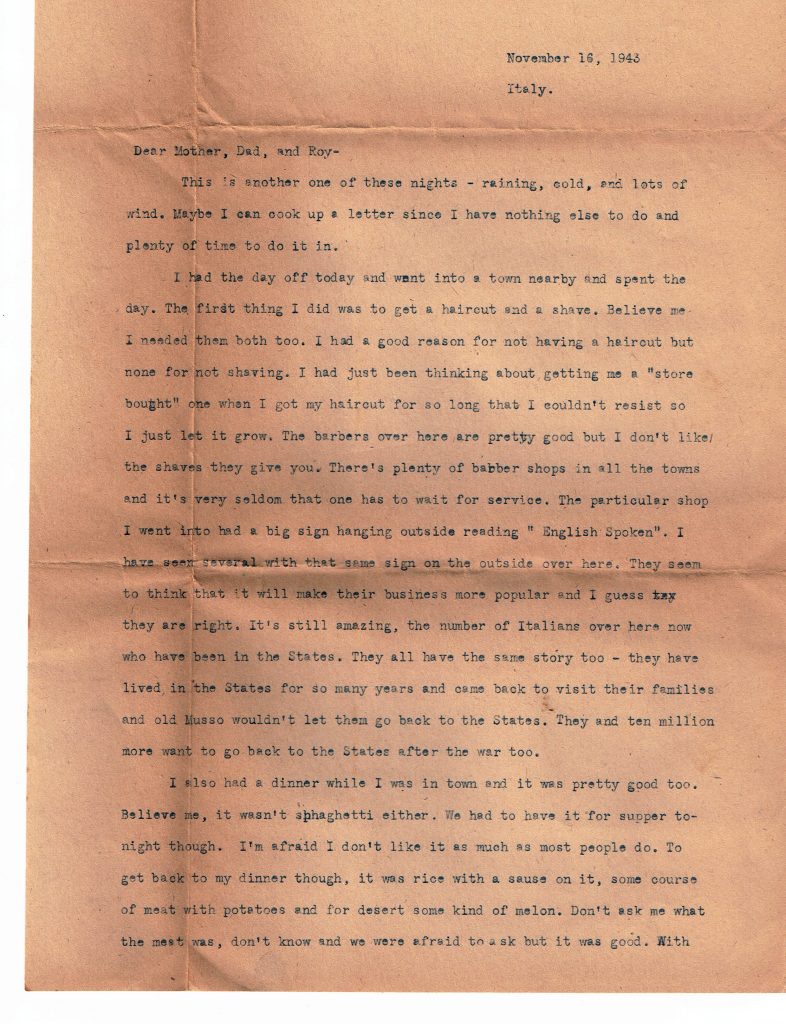

The next move was to Muddy Madna, just south of Termoli. We had steel mats on the runway but the mud was so bad the planes couldn’t even taxi onto the runway. The weather was very cold, too and it seemed to rain every day.

The first Christmas we were overseas, our packages from home did not arrive until March, April or May, the year after. Christmas 1943, we began receiving our packages around Thanksgiving that year.

We picked up the 99th Fighter Squadron while we were stationed at Foggia. The 99th was the first all-Black fighter squadron. We were told that they had flown some missions in North Africa. We carried the 99th with us all the way to Naples and the Anzio Invasion. Then they were transferred to the 15th Air Force where I understand they did a very good job flying cover for the heavy bombers.

On January15, 1944, we moved to the Capodicino Air Field near Naples. When we arrived, we must have been a pretty ugly looking outfit. We had been with the British all the time and we were using British right hand drive vehicles and a few German and Italian vehicles along with some regular GI equipment. We wore a mixture of British and American uniforms, so nobody really knew who we were. The Americans had put a General Wilson in charge of the Italian peninsula. He was tough about uniforms and military discipline. He also put a curfew in effect for both soldiers and civilians. Our boys had trouble with his MPs on a nightly basis.

On January 22, 1944, the Anzio Invasion was about to take place. I had to go to work in the early morning hours before daylight to help the Operations officers brief the pilots. On my to the air field, I was picked up by the MPs. I had my Luger with me and they took it and tried to get me to get into the truck they were using to transport prisoners. I tried to get the sergeant to go talk to the Operations officers to verify that I was out on official business. We had a fuss. They were going to put me in that truck and take me to Caserta where the MPs held their prisoners. I finally out talked them, but they took my Luger and wrote down my name, serial number and outfit.

After the invasion, we were very busy, day and night. About a week later, General Joe Cannon came into the Ops trailer and watched what we were doing for a while. During that time, Col. Bates told the general that he was tired of having to send an officer to Caserta every morning to get his men out of the MP lock up. He turned to me and told me to tell the general about what had happened to me the morning before the Anzio Invasion. I told the general about my encounter with the MPs. I said that I didn’t worry so much about having been stopped by them, but I really would like to have my Luger back. General Cannon turned to his aide, a colonel, and told him to see about getting my Luger back to me and to give me a pass that allowed me to be any place at any time, by order of the Commander of the 12th Air Force. The general signed the pass and gave it to me. I went to Caserta to the MP compound and got my pistol. When I showed the officer in charge the pass that had been signed by General Cannon, he did not know what to think. He returned my Luger and three extra clips of ammunition.

Because of the Invasion, we were working 20 hour days. We kept the Germans from bombing our forces by flying over the invasion area from daylight to dark every day. Some days I just slept where I worked and just went to chow when I could. To show you how tired I was, one night the Germans bombed the air field and hit the building two doors down from where I was sleeping and

I didn’t know a thing about it until the next morning.

We stayed busy flying combat missions for the 5th Army at Anzio until the breakout came. Then we hit bridges, railroads and convoys to keep the Germans from reinforcing and to keep them on the move. This was a trying time and we all stayed busy, day and night.

While we were at Capodicino, Mount Vesuvius erupted and I got an opportunity to fly over the side of the crater and around the ash cloud. It was something to see. There was a small village up on the mountain and some of the men from the 79th went up and helped the people move off the mountain.

At about this time, I was selected to go to the Island of Capri for a week of rest and recreation. It was a beautiful place. I floated into the famous Blue Grotto and that was great, but there really wasn’t much else to do on the island. I also got to spend one day at Pompeii. I was sort of glad to get back to the 79th.

The 5th Army captured Rome and the Germans pulled back and had gotten too far away to be within our flying range. At about this time, if my memory serves, we received notice that we were going to be transferred to the Pacific Theater and were ordered to pack everything up. The men were not happy about this since we had been in the Mediterranean for almost two years. After about two weeks, we were shipped to the Island of Corsica. I went by air with the first group so we could get the field ready to receive our planes.

Corsica was covered with cork trees and we found great places to swim and bathe in the mountain streams. We were located on the west coast of the island where we had three air fields. Several nights after we had arrived, the Germans bombed us. We were hit pretty badly, but an ordinance outfit that was located near us was clobbered and had many men killed and wounded. The native men on Corsica did not seem to like the Americans. The rumor was that the Corsicans would light fires in the mountains to guide German bombers into our locations. I think this was the only time the 79th was hit while we were on Corsica.

While we were on Corsica, the 79th picked up a squadron of French pilots. They were good pilots, but most of them did not speak English.

From Corsica we went by LST to the South of France, landing near the town of St. Raphael. Because our field was not ready, due to bombing attacks, we stayed close to the coast for several days. Major McEwen and Major Snowdon wanted take a few days to see southern France. I was asked to drive them. We got a command vehicle and took off. We went to Marseille and from there we went north, just sightseeing. We went into a town that was full of people in wheel chairs and who walked with crutches and canes. We did not stay long there. I believe the town was Lourdes.

From St. Raphael, we moved up the Rhone River Valley to Valence. This town had been passed by the allied troops, so we were the first they had seen. When we drove through the town, we were stopped by the people there and we were kissed on our cheeks by both the women and the men. There was such a knot of people there that we couldn’t move. I was stopped in front of the house of a school teacher who spoke English. He and his family were very nice to me.

The weather kept us from flying for several days, so we were allowed to go into Valence at night. I got some K rations and took them into the teacher and his family. After eating a meal with them, I started walking back to the field. On the way, I met a group of French men who turned out to be part of the FFI. They were picking up French collaborators and they wanted me to go with them. They kicked doors open and pulled men and women out into the street in their night clothes and took them away. I got away from them as quick as I could. They were tough!

The people of Valence adopted us and we them. The first Sunday we were there, I was on duty in Operations all by myself. I looked out and there were French men, women and children all over the field. I called the commanding officer and hold him about the crowd of citizens that that had just descended on our air field. He told me to do what I could to get them to leave. I told him that there were hundreds and he said that he would come on down. When he got there, he could not believe what he was seeing. He told me to call each of the squadrons and have two men assigned to each plane. All afternoon, the men of the 79th Fighter Group picked up little French children and let them sit in the cockpits. After that Sunday afternoon, we were much loved by the people of Valence.

During the time we were in France, we began to send our planes into Germany proper for the first time. In September, 1944, we moved from Valence to Bron Field near Lyon. While we were there, a mass grave containing the bodies of many Jewish people was uncovered. They had been killed by the Nazis before they left the area and their bodies had been dumped in a bomb crater.

Due to a lack of fuel for the planes, we could only get a few missions out every day. The 12th Air Force was flying fuel to us in B24s and B19s from Foggia, Italy. The allied forces in northern France and Belgium were moving so fast that most of the fuel was being used up there. That left plenty of time for me to go into Lyon. We had great food there and plenty of drinks. After a few weeks at Bron and Lyon, we were sent back to Italy where we were reunited with the Desert Air Force. It was like old home week.

I was flown to Fano in our B25 with several other men to get our new field ready to accept our planes. The field was an old Italian base. The rest of the outfit came by LSTs, landing near Naples and then trucking east across the mountains.

Fano was a hot spot. We were the nearest air field to the front. On one occasion, I was working the tower and we had maybe 30 crippled planes come into our area. They were part of the 15th Air Force, which was stationed at Foggia at that time. They had been in a hell of a fight and some of their planes had wounded men aboard. It was 30 minutes of my life that I will never forget. We got all the planes down safely except one that crashed about a mile short of the runway.

One evening, after we had closed the tower down, my operator turned in the log book and I discovered that one of the planes was not accounted for. I called the squadron and was told that the pilot had gone to see his brother who was a bomber pilot stationed somewhere south of Fano. He was supposed to spend the whole day with his brother. To be sure, I had the tower operator crank up the generator and see if he could raise the pilot on the radio. By then, it was dusk dark, but I could hear a plane far off in the distance. I called the pilot on the radio and, sure enough, it was the missing pilot. He was having trouble finding the air field since it was getting dark. We went back and forth trying to figure out his location. We shot flares, but to no avail. Finally, I remembered that there was a radio outfit that monitored all radio traffic in the area. I called them and they told me that all they could do was give me an azimuth, but that they could call another station and they might be able to triangulate the missing pilot’s position and bearing. They did this and we were able to give the pilot a heading to our air field. I got some mechanics to put a fifty gallon drum of fuel on a jeep and empty it along the runway. I told them that I would signal when the pilot was ready to come in. When they started the fire, the pilot was able to line up and land his plane.

Just as we put the fire out, the group commanding officer came down to see what was going on. I got chewed out because of the fire. But the next day the squadron commander and the pilot came by and told the CO what we had done to get the pilot and plane down. I think I saw the 79th’s commanding officer looking at me in a different light, but it was the team work of the tower operator, the mechanics who started the fire and the radio men at the other stations that got the plane and pilot down safely.

While the 79th was still at Fano, some allied troops were bombed by friendly fire. The Air Corps sent out a regulation that required personnel be placed with allied troops to point out targets for close air support missions and to prevent our troops from being bombed or strafed by our planes. Col. Martin and I went to the MORU Headquarters to discuss our using a forward air controller when our planes were used for close air support. The officers at MORU took us up to the front and showed us the set up there. They told us that they would be happy to have forward air controllers with them at the front.

When we returned to the outfit, we outfitted a jeep with flares, radios, panels, food, maps, etc. I went back to MORU where I stayed for about a week while our squadrons were being sent to northern Italy bombing bridges to keep the Germans hemmed in and to prevent their escape across the Alps. When we got a target for close air support, I was able to go up to the front and we were able to hit the target with no trouble. I went back and forth to the front for several weeks and made enough time to be called a forward air controller.

In early 1945, the services were giving their soldiers 30 day leaves so they could return home for a while and then come back to their outfits in Europe. I was one of the first to get leave approved. I was planning to get married while on leave at home. I don’t remember if I was at the front or at the 79th when I realized that I was getting sick. We had been taking Atabrine for malaria and our skin was yellow, but when I saw my eyes were yellow and my urine was red, I knew something was wrong. I couldn’t keep any food down for about a week. A medic friend told me that he thought I had hepatitis. I was sent to a couple of hospitals in Italy for about a month while I recovered.

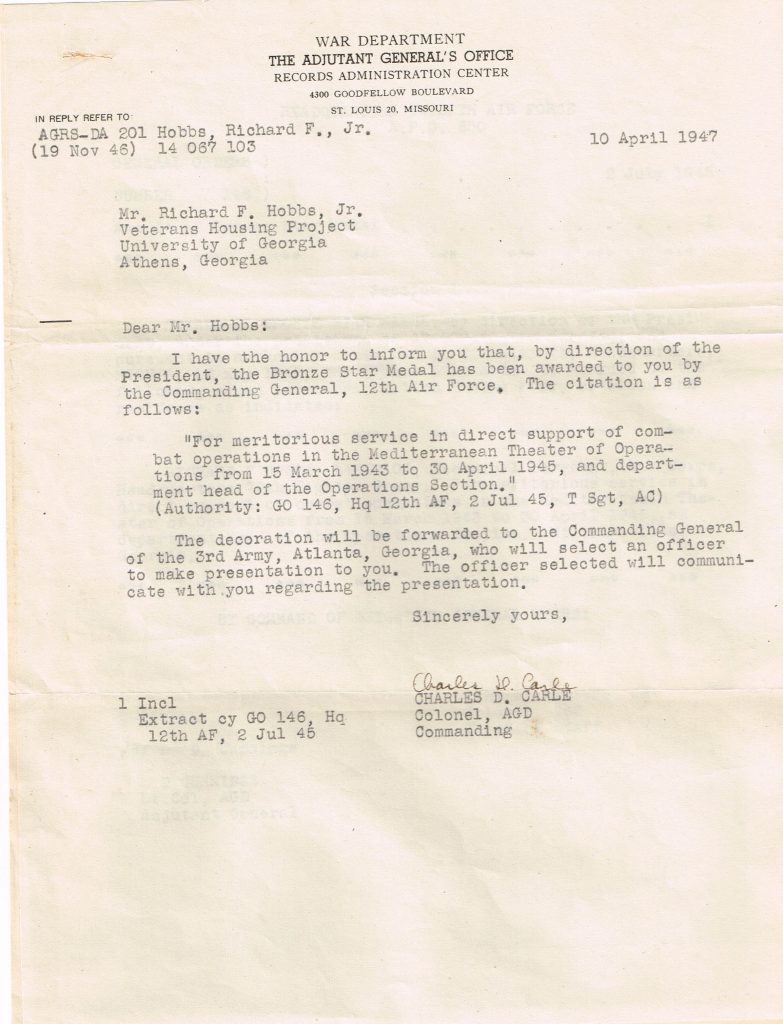

Luckily, my illness did not affect my leave and I was able to return to the States in April, 1945. I married my hometown sweetheart on April 19, 1945. I was not required to return to the 79th Fighter Group. I had other assignments in Miami, St. Louis and Washington D.C. before I was separated from the service in September, 1945.