Henry Kent

“The chapters of pilot Henry Kent’s life/ from flyboy to cartoonist to educator…and more,

by Steven Mayer of the Bakersfield Californian, and the Kent family”

by Steven Mayer of the Bakersfield Californian, and the Kent family”

Some folks have a strong business resume; others have a stellar life resume.

It seems Henry Warrington Kent may have fit the latter description — in three chapters or more.

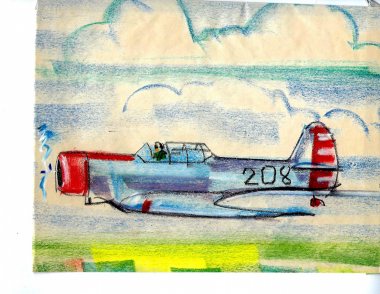

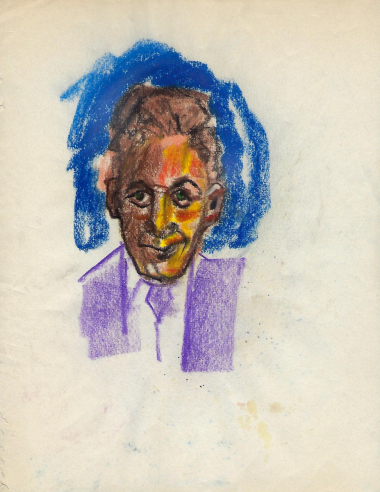

A World War II fighter pilot who earned nine Bronze Stars, a Distinguished Flying Cross, an Air Medal and eight Oak Leaf clusters, and more, the handsome Jacksonville, Ill., native later sold cartoons to the Denver Post, before earning his master’s degree and becoming an educator teaching science and physics at the high school and university level — yes, and more.

The war hero, scholar, scientist and family man who spent the last quarter-century of his life wintering in Bakersfield and summering near St. Louis, died March 20 at his Webster Groves, Mo., home surrounded by family. He was 96.

“My father never talked about the war,” said his daughter Karen Waller. “We were never clear on his medal count until we found his discharge papers.”

“He was an Illinois flyboy,” she said, “which he hated to be called.”

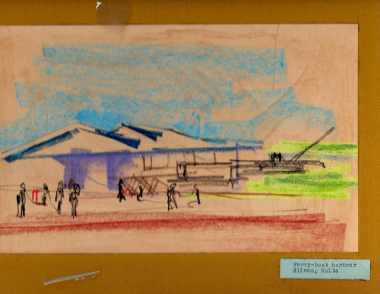

After enlisting following the attack on Pearl Harbor and training for months, Kent was deployed to Egypt on his 20th birthday in January 1943. Amazingly, he served first under British command, as the Brits were well-established in North Africa, long before the United States — which joined the war effort late due to strong isolationist sentiment among many Americans.

He would fly more than 70 missions in the North African theater, Waller said.

His ultimate commander at the time was not an American general, but a Brit, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, known by the troops, the public and the press as Monty.

“Monty was all business,” Waller remembers her father telling her. And the stress was extreme for pilots, whether they were escorting bombers on long missions or patrolling the coastlines of Sicily and Libya.

Only 20 percent of Kent’s squadron survived the war, Waller said. It was a gut-wrenching statistic, one of many that would leave Kent with a sense that there is no glory in war, that it was a mean though sometimes necessary business. But it wasn’t to be treated or talked about like some jaunty adventure or ego exercise.

Kent would see action over Libya, Tunisia, Sicily, Naples and other areas. And he would survive crashes, a loose live bomb during one landing and other disasters and near disasters. He even witnessed a suicide by plane by one of his comrades, an incident that also hit him hard.

By the time he arrived home for Christmas 1943, he was a changed man. But the course of the war was changing, too, thanks to Kent and millions of other men and women who had donned uniforms to oppose the fascist Nazi dictator and his armies.

During his time back in the States, he met and married Mildred “Millie” Mason, after knowing her for just a few weeks. Romance was often hurried during the war years, when young men didn’t know if they would live to their mid-20s and young women couldn’t know for sure if their lovers would ever come home.

Despite their whirlwind romance, Henry and Millie would remain married 75 years.

Despite his heroic performance in the North African campaign and the invasion of Sicily, Kent went back into the heat of battle in January 1945, when he was deployed to France.

But something in him had changed, he told his daughter years later.

“He told me he lost his edge,” she said. “He was in love and he had someone waiting for him at home. Now he had something to lose.”

By the time it was all over, the World War II fighter pilot had flown some 140 missions, extending his reach to Central Europe, the Rhineland and other regions. He turned down offers to stay in the Army Air Force and make a career of it.

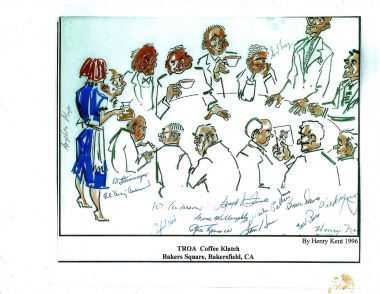

Instead, he went home, started a family, and “exercised his creative side,” his daughter said, selling cartoons to the Denver Post.

He soon went back to school, earned a master’s degree in physics and became an educator, teaching science and physics at the high school and university level.

“Growing up I didn’t realize how much of a bad ass my grandpa was,” said Kent’s granddaughter Cassie Packard, who grew up in Bakersfield and moved away to go to college. She now lives in Michigan.

“I saw my grandpa as an old man who told long stories, loved his candy and enjoyed hearing my grandma play the piano,” she said. “Looking back on it now that I’m older, I realize he was such a smart, hardworking, brave and fearless man.”

He never bragged about his accomplishments, she said. And yet he was incredibly accomplished.

He helped start the Avionics program at Parks College of Engineering, Aviation and Technology at St. Louis University, his family said. And he worked decades with McDonnell Douglas and Emerson Electric “using that beautiful mind,” his daughter said, working on perfecting the F-15 and F-18 jet fighters.

As a child, Packard said, she was artistic, and her grandpa always encouraged her to stay with it.

“I loved sneaking into his bedroom where he had an art studio,” she recalled. “I would sneak in there and flip through his sketchpad and draw some things to surprise him with later. I loved hearing his feedback on my drawings. It would always make me strive to be better.”

She went on to pursue art in college and fell in love with photography. She now has a thriving wedding and family photography business, and believes she gets much of her talent from her grandfather.

“I didn’t realize all the amazing things about my grandpa when I was little,” she said. “He was just my grandpa. But now he is an example to me to never let fear stop you from achieving your potential.”

Some 26 years ago, Bakersfield became his retirement home. He loved it.

“Once you go to Bakersfield, it’s hard to leave,” Waller said. “That’s what he told me.”

But in some ways, he could never escape the war.

It took a huge toll on him, his daughter said.

He was near the end of his life when he told Waller about strafing a group of what he believed to be German SS troops — the elite members of the German army — on a hillside in Sicily.

“They were all dressed in black,” he told her. The signature SS uniform.

But when he came around for a second pass in his fighter, he first saw the hooves of a dead horse. Then he saw the casket. And the world crashed in on him.

He realized in horror that it was a Sicilian funeral procession.

That incident and others left him believing, deep down, that he was guilty of a sin that could not be forgiven.

“I tried to tell him that through his actions, he helped save millions,” Waller said.

Indeed, if Hitler hadn’t been stopped by the gargantuan efforts of the Allies in World War II — and men like Kent — millions more might have perished in the concentration camps and the Nazi gas chambers and on the battlefields of Europe and beyond.

What a life he led. What a sacrifice he made.

“My dad, huh?” his daughter said. “What a guy.”