Walter L. Manning

A 2012 interview with pilot Walter L. Manning at the Iowa Gold Star Military Museum, transcribed by his daughter Julie Jackson

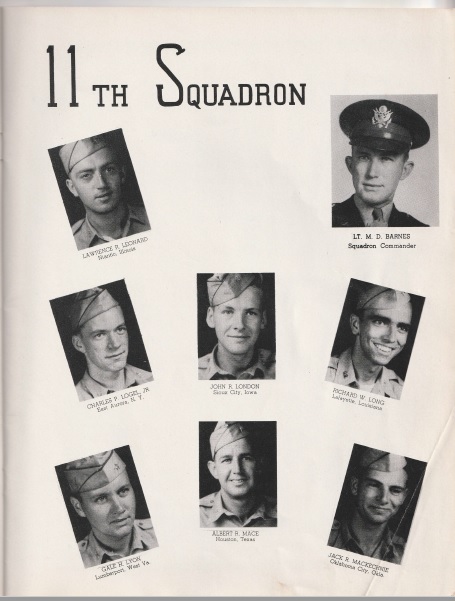

Part #1 Walter L Manning, 86th Fighter Squadron

Enlisting

I was under the draft age. At that time, jobs were kind of hard to find. I’d been laid off from the survey party on the Highway Commission. They were drafting people who had wives and children, and I thought, well, I’m single and young so I just decided to enlist. I thought I’d get what I wanted by enlisting ’cause I wasn’t even signed up for the draft. When I went down to Des Moines to enlist, they said, well, we can’t guarantee you what you’re going to get by enlisting, but usually if you enlist, you get what you want. I said I want to be a mechanic in the Air Force.

After about 10 days at Fort Des Moines, they finally swore me in, and sent me on a train, and I got in the truck, and I was in the Corps of Engineers. I said I’m not supposed to be in the Corps of Engineers. “Well, this is the best outfit in the army.” I said I was supposed to be in the Air Corps, but I ended up in the Corps of Engineers instead.

March is not a very good time in Iowa. It was wet, and everybody smoked in those days and kids coming in would throw their cigarette butts on the ground. You’d get up at 4:30 in the morning for roll call. And then you went around and picked up these cigarette butts that people all threw on the ground, and they were really soggy. It wasn’t a happy experience.

For some reason I didn’t pass the physical the first time. It was something to do with, I think, sugar diabetes, and whatever it was I went and took the test about three or four times and finally on a Friday, they said, well, you passed, and I said what now. They said, well, you come back Monday and take another test. I said to this Sergeant, give me my enlistment papers. I’m going to California and work in a defense plant. I said I’m volunteering and now I’m ‘unvolunteering’. And so he went in to the major’s office, and I could hear the major saying something about we are fighting a war and you were supposed to want to get into it and all this and that, and they came out, marched me down the hall where there were people who were being drafted, and they said get in the back row, and I raised up my right hand and they swore me in. By that time I was kind of peeved at the army because they didn’t send me where I wanted to go, and they kind of hassled me for a while. The Corps of Engineers was alright, but it’s really worse than being an infantry soldier because you got to work along with fighting.

Army Basic Training Fort Leonard Wood, MO

Activities: Close order drill, Combat films, Long Marches (10-15 miles), Bayonet Drills, Rifle Range, Building and Tearing Down Bridges, Guard duty, KP, Calisthenics

I got my orders to go to Clerk Headquarters Company in Fort Leonard Wood. The guy behind the counter at Fort Des Moines who was issuing pants and jackets and shoes, would look at you and say, “Number nine shoes”. Never measure your feet or anything, so when you got to Fort Leonard Wood about a third of the time you were taking stuff back and exchanging it because it didn’t fit. If you asked for something, he’d give you just the opposite. All he was trying to do was get this clothing out in circulation, I think. That way they were moving it. So then when you got down to Fort Leonard Wood, you went someplace and exchanged your shoes or exchanged your pants. It didn’t look very efficient, but that’s the way he measured you just by looking at you.

During Army Basic Training you got a lot of close order drills, and you got a lot of practice with a bayonet on dummies, a lot of long marches and building bridges. We used to have a contest between the different squadrons on building bridges. If you got your bridge built first, you won. The other people had to tear it down. Otherwise, once you built a bridge, you had to go back and tear it down and put it back on the truck. So, everybody would go real fast trying to win so you wouldn’t have to tear a bridge down. So it’s kind of a competition and sometimes they would say the winner would get a three-day pass and so that gave you more incentive to build a bridge.

In the Corps of Engineers there’s a lot of hard work. I think it lasted about three months, but seemed like a lot of it was close order drill. Some of the boys just didn’t do very good at close order drills. You had all ages. We had people in our platoon who were 39 years, and there I was like 20. I mean ’cause a lot of the engineers and conductors on the railroad and firemen and stuff was going into the Corps of Engineers because that’s where they were going to use them. So you had all kinds there. It was a good experience, $21 a month. And then you had $6.50 for insurance every month. So you didn’t make a lot of money.

While I was there, this building was next door, and so, I went over there and took the test to be a pilot. I didn’t think it was very hard, and the guy said, “Well you passed”, and I said, “What happens now?” He said, “They keep you here until they need you and then you go into the Air Force and learn how to fly.” So I went back to the office where I was working and this captain said “Walter, what have you been doing?” I said I went over there and took a test and passed it. They said I get to be a pilot. He said you didn’t ask me if you could go over there, and I said, well, it’s noon. I thought I could do what I wanted on my noon hour. Oh, well, you should have asked me. I said, well, it’s too late. They said that I did pass it, and you got to keep me here. You can’t ship me any place until they get ready to take me. So I worked for him then until they called me up to go to the Air Force (Air Corps).

Part #2 Walter L Manning, 86th Fighter Squadron

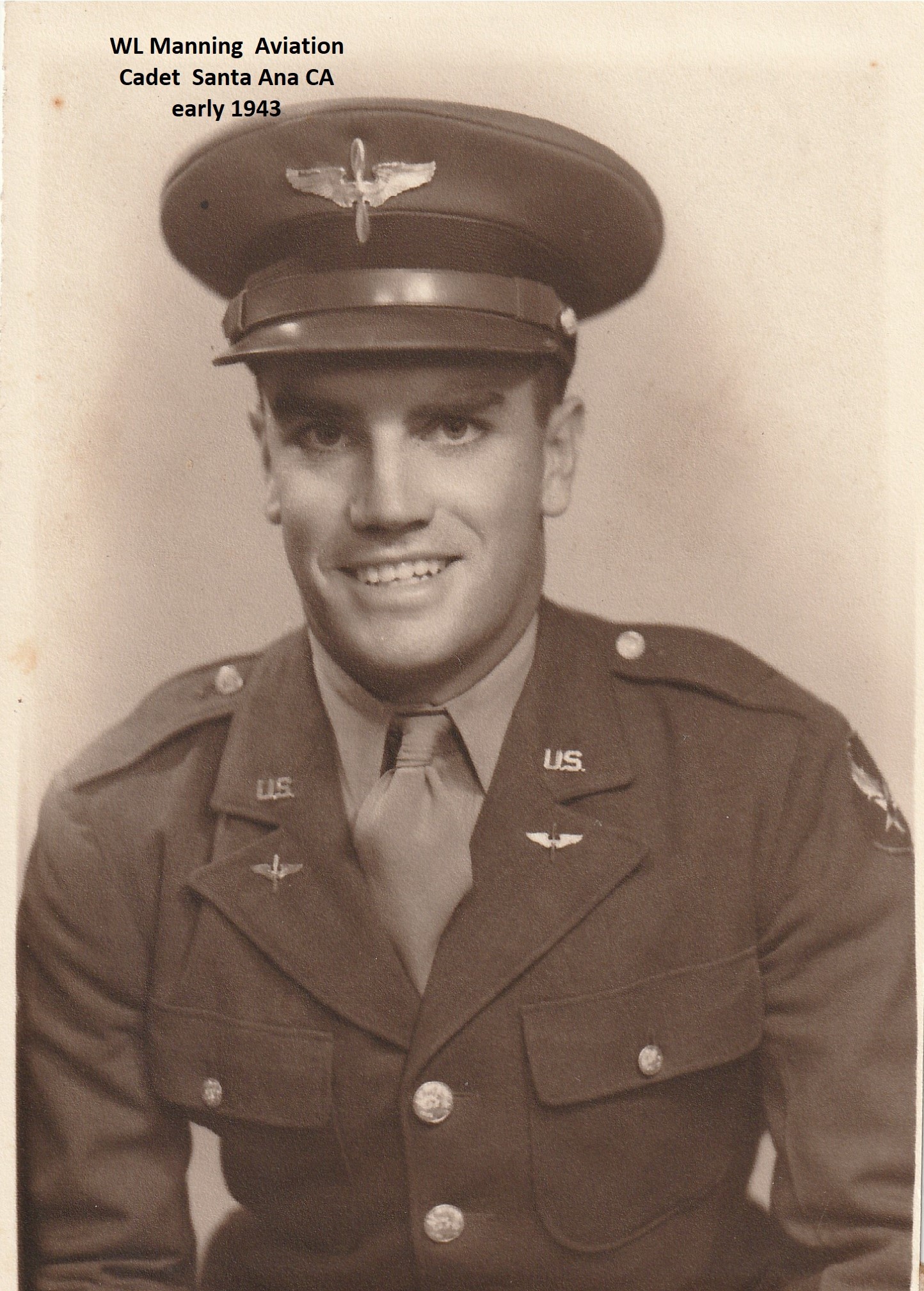

Preflight School Santa Ana, CA

Activities: Test for students to check qualifications for flying, marched to mess hall and to PX, Close order drills, Calisthenics, pass in review parade every Sunday, Ground school courses daily.

Preflight training in the Air Force was at the Santa Ana Air Base. There you were quarantined for the first 30 days because they didn’t’ want people coming in to spread any disease one of them might have. This area was like a city block. It had two or three barracks on it. It was a new field; no grass or anything, just mud and clay. They would march you if they wanted to take you someplace. For 30 days, you were there until they saw you weren’t going to catch something. Then you started their ground school. They marched every place you went, get in formation, march to ground school, march to the PX, march to dinner. And they wanted you to sing songs and be gung ho.

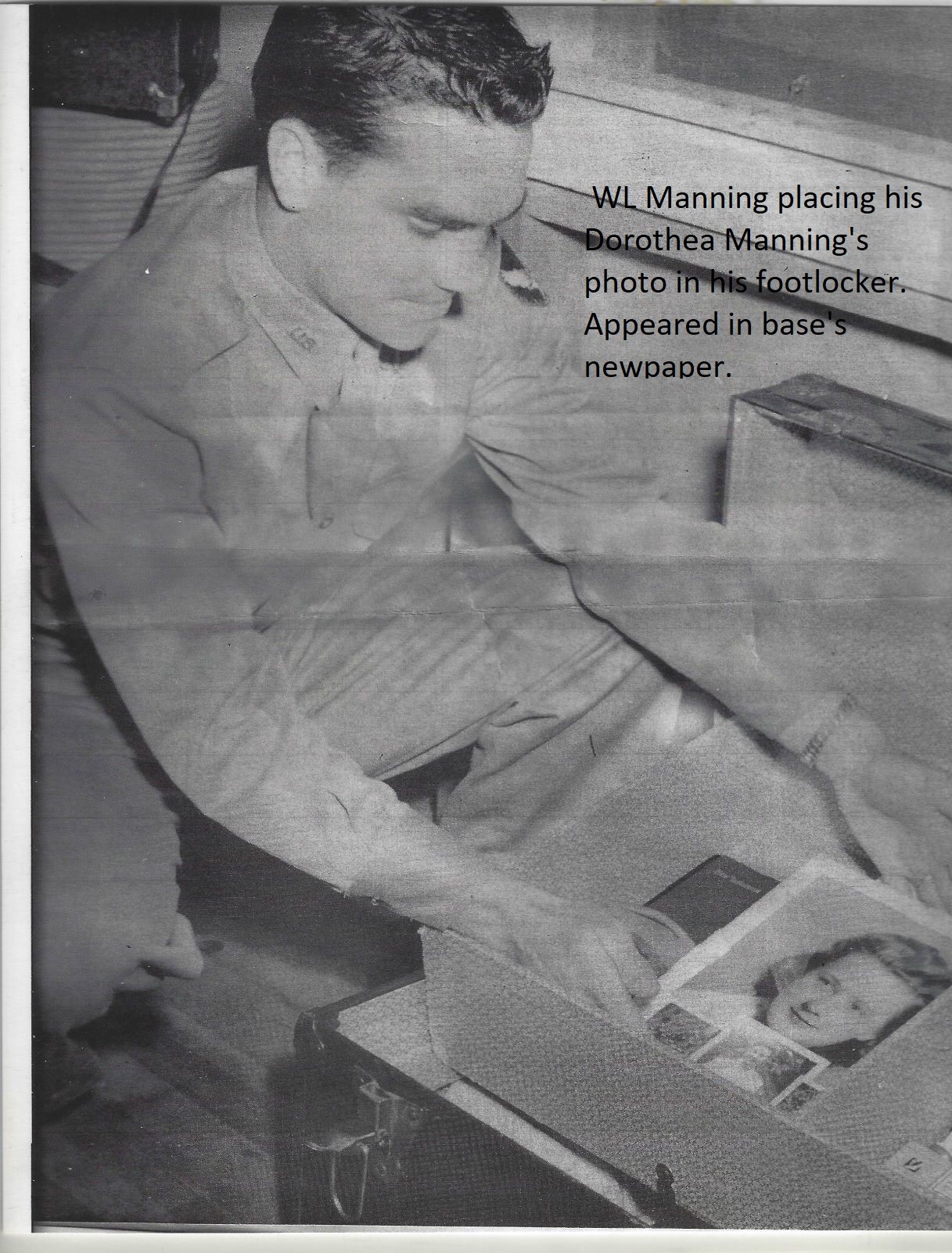

I married Dorothea Ellen Thornton (girlfriend from Adel, IA) at 6:30 p.m. Sat. Jan 9, 1943. Honeymoon in Santa Ana from 6:00 p.m. Saturday until 10:00 a.m. Sunday, and back to the base for Sunday Parade.

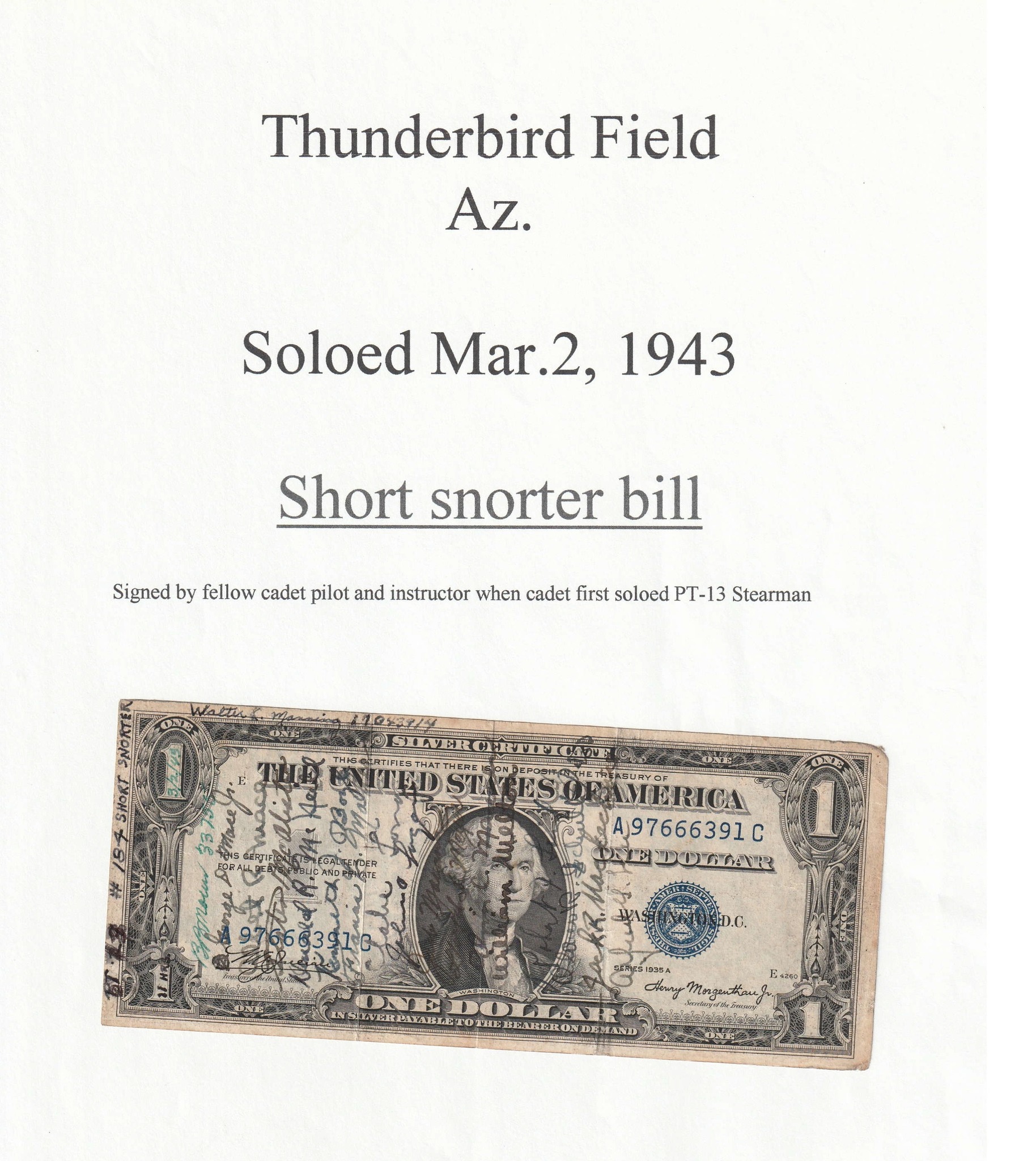

Primary Training Thunderbird Field Glendale, AZ

PT 17 Stearman 220 HP First flight 2/19/43

Soloed 3/2/1943. Graduated 3/8/43 63 hours flying total

I took Primary Training at Thunderbird Field in Arizona. I think that the field was formed by something to do with the movie industry. It was kind of like a flying club before the army took it over. I got 60 hours in a PT-17 which had an open cockpit. I had never flown, and our first time up, it didn’t seem to me like it amounted to that much. You did a lot of maneuvers in that airplane. It was a biplane, and it is the only plane we ever did a lot of spins and stuff in.

You are supposed to solo by 12 or 14 hours, and I had 12 hours, and I hadn’t soloed, so they gave me to an insurance salesman. All these instructors were civilian pilots, and this man was B.B. Moeur out of Arizona. He says, “Walter, what’s your problem?” I said “Well, I am pretty good one day. My instructor says if you do this good tomorrow, I’ll give you the airplane, but then he tells me how much the airplane costs. He never says anything about my life. It’s always how much the airplane costs, and he never lets me solo.”

He said, “Don’t worry about it. If you have trouble finding the ground, I’ll build a platform out there, and you just drive past and step off on the platform.” So we flew a couple of days, and he did most of the flying, and he just talked continually. This one day, on this big, big field, he said taxi over to the marker that showed which way you took off. I taxied over there, and he got out and he goes over and gets down on the ground, lays in the shade. I’m sitting there. The airplanes are running, and pretty soon he looks up and he comes over and says, “what are you doing?” I said, “I’m waiting for you.” “Well”, he said, “Oh, I forgot to tell you, go shoot 3 landings and come back and get me. I’m going to take a nap.” So I shot 3 landings and taxied back over, and he comes stretching like he’d been asleep. He said, “How did you do?” I said, “weren’t you watching me?” “Oh no”, he said. “I knew you could do it.” He helped me have confidence. You know my first instructor was a nice man, but all he ever worried about was what that airplane costs. That’s it. Every day this costs… I don’t know how much, but a big figure for us in those days. After the war I thanked B.B. Moeur.

Primary training included all kinds of class work along with flying. At this place, if you got 10 demerits in a week, you had to walk one hour on a Saturday or Sunday. 55 minutes out of the hour, around this grass area and then they finally moved it out onto the runway because we didn’t work on Saturday and Sundays. If you were a class officer, you had to go out there and see that the Cadette walked two hours for the demerits he had received. I got through without ever having to walk an hour.

You had 11 people in your sleeping area, and each one had responsibilities. One was responsible for the beds, and one for the bathroom. You could get demerits ’cause your name was up there. So we used to put toilet paper up in the faucets so they wouldn’t drip down on the basin because if there’s water in the basin, they’d get a demerit. So, after everybody used the faucets, you’d poke toilet paper up there so they couldn’t leak, then wipe it out dry.

It was a deal where upperclassmen dominated, and if you were the underclassmen, you were supposed to stand really at attention. When you talked to them, act like they were a big wheel, which they weren’t, but that was the way. And when you went in to eat, you couldn’t touch the railing where you had your tray. You could just slide your tray. You couldn’t talk to any of the girls behind that were serving or anything because you were supposed to be kind of at attention the whole time you were going through. They’d give demerits for anything you did that they didn’t like.

It was fun because, you know, you were young, and you had people that you didn’t know. That was a good thing about the Air Force. You moved about every three months. When they do it, they take the alphabet and cut it in half so most of the people I flew with were L’s and M’s and O’s, and the people I know were all like that, and they go to the next base. You got half of them you didn’t know, but half of them you did.

Part #3 Walter L Manning, 86thFighter Squadron

Basic Flight Training Gardner Field, Taft, CA

BT-13 Valiant 450 hp First flight 4/20/32 Graduated Basic 6/16/43 80.0 hrs. flight time

I took basic training at Taft, CA up near Bakersfield. We flew the BT-13. It had a fixed landing gear, and a covering over the cockpit. It was supposed to be a kind of dangerous airplane because they said the tail would fail. I had one instructor that said, “I want to show you that this airplane is a good airplane.” I don’t know how high we went up, and I said, “What’s going to happen?” He says “I’m going to kick it into a spin. I’m going to put my hands on top of my head. If I holler jump, you jump because I won’t be here after I holler jump”. Sometimes the tail did come off on some of them. That’s what he did. He put his hands up like that, and I sat there, and pretty soon the airplane came out into a kind of a dive. He was just showing me that if you had enough room, it would come out of anything it was in. But he impressed me when he said “If I say jump, don’t wait for me to say jump the second time ’cause, I won’t be here”.

Some of the lieutenant Army instructors were pretty rigid people, and others were happy go lucky. I landed one time in a B-13, and we came in and turned, and I was turning into the landing and here comes another instructor with a student who cut inside of us. My instructor says “Don’t let him cut inside of you. Give me the airplane. He’s not going to land in front of us.” So I let him fly, and he gave a little more gas and got ahead of that guy and landed. I’m just sitting there not thinking about the dangerous part of it, but you had those little egos, even among instructors. It probably was stupid. I just went ahead and let him land.

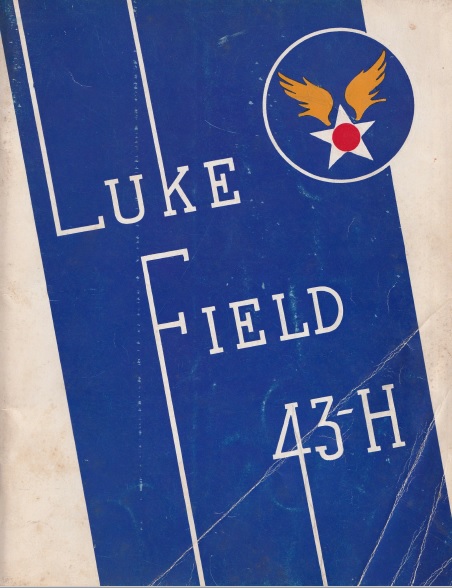

Advanced Flight Training Luke Field, Phoenix, AZ

AT-6 Pratt & Whitney and P-40 600 hp 104.3 hours flying

I want to tell you a story about the training in AT-6’s. I think that would have been in Advanced. This instructor says I’m going to take you out. He had three students with him. He said that what we’re going to do is get in line abreast, then fly it through clouds. We didn’t have a lot of training instruments, and actually, he probably shouldn’t have done it. Two students that I knew really well were always telling me how good they were. I mean they were the top. I never thought I was really that good, and I was over here on the right. This instructor is here, and they are over here. So we’re lined up abreast. We went into this cloud which wasn’t very big. All you were supposed to do is keep heading out, not go up or down, just fly straight. When we came out, the two students over here were over here on my right. You should have heard the instructor. He was livid. The funniest part of it to me was they were always telling me how good they were. I was where I was supposed to be, but they had passed both of us in this cloud and were over on the other side. I didn’t at the time really realize how dangerous it was because I was getting a kick out of this instructor. He was just really chewing them up one side and down the other on how they got from the left side over to the right side in just a little bit of cloud. I have no idea how they did it, but they could have wrecked all four airplanes. Usually the kind of a guy who did all the bragging was really probably one of the worst ones.

Flying airplanes in training was like a flying circus sometimes. When you were not doing anything, the best thing was to watch the other people land because they’d crow hop, you know, hit and bounce going down the runway crow hopping. Once in a while, you’d see something really bad, but most of the time it was just little things. Maybe they’d cartwheel on a wing tip or something. I do remember one time that one landed on top of another one. Usually you didn’t know those people, so it didn’t really impress you one way or the other that much. It’s just something that happened. There were quite a few accidents, and usually someone would spin in on them, especially coming into land. They would pull the nose around too much, and it would roll over on them and go down in the ground. That was one of the worst things that would happen because when you’re that close to the ground, you have to be pretty good to recover. I don’t have any idea how many were killed while in the three trainings. They lost a few, but not any great number.

Fighter Training School Pinellas Field- St. Petersburg, FL

10/5/43-12/15/43 P-40 Training Flying Hours 75:45

I went to fighter school down in Florida at St. Petersburg. There you got 60 hours in a P-40, and you did formation flying, dive bombing and they had a little island out there that had some dummy smoke bombs to gun down. You also went to Gunners school, aerial gunnery and shooting targets on the ground. At the end of 60 hours you were supposed to be a combat pilot.

Part #4 Walter L Manning, 86th Fighter Squadron

Airplanes We Flew

The airplanes were the main difference between the Primary and Basic and Advanced training flying wise. The airplane always had a little more power, and in Advanced you had to put the wheels down, and by that time, I think, the 13 had flaps. The AT-6 had flaps that slowed you down whereas the Stearman didn’t have any of that. The worst part about the Stearman, it had a real narrow landing gear, and then with those kite wings on it, the wind was blowing it, you had to be real careful taxiing on the ground ’cause it wanted to go one way or the other with the wind catching it. You didn’t have to worry so much about the 13. It was a wider landing gear. The AT-6 landing gear wasn’t so wide, but it was an easy airplane to fly. With each plane you had more things to think about.

The BT-13 didn’t have a lot of horsepower, in the 200 hp probably. It wasn’t fast but was an improvement over the Stearman. In Advanced I flew the AT-6 which they used for a long time after that as trainers. Even when they were into the Jets, they still used some AT-6’s as trainers. They had a folding landing gear, another thing you had to think of. When you’re landing gear folds, you don’t want to try to come in and land with a folded which some people did.

One of the problems with the P-40 was that they had a VHS radio and a short-wave radio. So a lot of times, especially in the States, when you were training, you couldn’t hear the other guy who was coming into land because he had a different kind of radio. I don’t remember any problem with that overseas, but it was VHS—line of sight transmission.

When I was in Advanced, they gave me 10 hours in a P-40. I’d never started it or anything. I sat in it, and the nose on the P-40 juts up pretty high. That’s so when you come into land, you’ll know how far the nose should be so you’re in a landing position. I had read some books, but never taxied it or anything. They pulled me with a tractor out on the runway, and we sat 45 degrees to the runway. This officer crawled up on the wing, and said, “You know how to start it?” Well, I knew how to start it, but when he asked me that kind of question, I was kind of hesitant. He flipped a couple of switches and said, “Now I’ll energize it on the outside.” It didn’t have a starter. He said, “When it starts, don’t check your mags”. Most of them had dual mags. You were always to check right and left Mag to see how far the revolution would fall off. That really threw me. I mean, ’cause, that was supposed to be a Bible thing. You always checked your mags. He said, “don’t check your mags.” So he’s getting me pretty upset, and he said “when it starts, start down the runway, and if it coughs, just shut the switch off and pull the wheels and belly it in.” So I started down the runway, and everything seemed to be fine. I had a list on my knee what I was supposed to do: fly an hour, get to 7500 feet, do certain maneuvers. Every time I’d pull the nose up, the coolant would come over the windshield where I couldn’t see, and I’d nose it back down. In an hour I got up to 5000 feet finally. I should have taken it back, but I was flying a fighter, and I wanted to fly it. As long as I‘d nose over and fly like that, it didn’t boil, but as soon as I tried to climb, it boiled. So I never did get up to 7500 feet. I brought it back in and landed. He told me when I landed to just let it roll off the side and shut it off. They pulled me back in. I went back to barracks, and I told the guys maybe we should go to bombers. These fighters really aren’t very good, but later I flew it eight or nine more times, and I don’t remember a thing about flying it at that field after that. Just that one. Then in Florida, I flew for 60 hours in it down there. It was a nice airplane, but it was a little obsolete.

The planes in Florida, I think, were P-40 Ns. I’m not really sure. They were so much better than the ones in Arizona. Arizona ones were war worried. Some would come back from combat not in very good shape. They had, I don’t know, 15 or 20, but they would only have one or two that were able to fly that day. Down in Florida, the airplane was fine and the only thing I was surprised about was night flying. Down there we came in over a highway, and then down at the end of runway was Tampa Bay. They did not call it Tampa Bay, but it was part of Tampa Bay. You came in over the highway, and these cars were going along here. You’d be coming down, and I know they would think you were going to land right on top of them.

On the P-40 the exhaust is along the sides. When you cut the throttle back, it’s like Roman candles coming back over your hood. You had to carry a little bit of throttle all the time. Otherwise, if you just pulled it back like that, it just sparked. It just spfsst!. And then, of course, you couldn’t see very good. It had a real little narrow landing gear. Even after hitting the ground, you had to keep guiding it ’cause it wanted to go around on you. The landing gear was really the only thing I had against it.

Part #5 Walter L Manning, 86th Fighter Squadron

Airplanes We Flew Continued

You didn’t have to worry about any of that on the P-47 which I flew later. You’d just bring it in, and as long as you get close enough to the ground, ’cause it was so heavy when it stalled out. If you were high, you would just drive the struts right up through the wings. The P-47 had so much weight to it. The P-40 was the early fighter, and they never really brought in another engine. If they didn’t like the P-51, they could have put a different engine in it. It would have been a lot better airplane. I don’t remember what engine it was. It only had like 1250 hp, I think. The P-40 was the best airplane I had flown up to that time.

The P-47 was faster than the P-40. It was heavier. It had a radial engine, and the P-40 had an inline engine to which you add coolant. That was a bad part about the P-40. You know the first time I flew it; the coolant gave me trouble. If you had one little rifle bullet in the coolant line, you were done. With the 47 you could have the cylinder shut off, and it was still flying as long as you didn’t run clear out of oil. It was a lot more rugged. It was not made for what we used it for. It was made for 30- or 40,000-feet escort, and we used it for down on the ground. It had oxygen masks, which we wore all the time. I don’t know why because we’re never up very high, but we always wore oxygen masks. Sometimes thinking back, you think maybe they could have just not put any oxygen in there as they knew you weren’t going to go over 10 or 12,000 feet, but we always strapped it on & used it. It was automatic. When you were closer to the ground, you didn’t use as much oxygen, but always used it that way. That was the way you were trained, and that’s what we always did.

I said that the P-47 was the best aircraft for what they were doing they had in the war there. The P-51 gets a lot more credit, but the 51 came after the 47. At the time I was over there, they had what they called an A-36. It was a 51 with dive brakes, but it was the one before they put the new engine in the 51 that made it so popular. I don’t know that much about engines, but once they put that new engine in that 51, it could get further away from home. It could escort further, and it was fast. It was a real good airplane for escorting. It wasn’t as good as the 47 for doing ground strafing because it had an inline engine. The 47 was just a workhorse. You’d have thought that they’d have wanted to make it lighter since it’s going to be down next to the ground. It weighed 16,000 pounds. We carried two 1000-pound bombs under the wings, a belly tank of gas plus all the other armors you had. I never had it when I was shooting rockets.

I have never flown a P-51. That’s one of the things I wished that I had got to fly. One reason I probably wasn’t thinking about it those days was that I trained with kids who flew the A-36’s, and some of them really hated that airplane. With dive brakes, they were supposed to be able to dive straight down. They didn’t dive straight down, but that was the idea of it. So it’s going to be really accurate, but they were going so slow that the anti-aircraft fire was hitting a lot of them. They were losing a lot of airplanes, a lot more than the rest of us were. I had a wingman say one time we’re doing 550 going downhill going into bomb something. We went in a hurry and got out in a hurry. In one of my books, I saw some information about the Tuskegee Airman, the 99th, that were with us longer than I thought. They were there when I got there, and it seemed like it was only a couple months, and they weren’t with us. So I don’t really know anything about them. They got a lot of good publicity, and I’m sure they earned whatever they got, but they flew the 51. The 51 was America’s airplane in the latter part of the war. If you pick up a book, the 51 is the one always mentioned.

I always thought the 47 was the workhorse. It’s like the C-47 twin engine that transports. The C-47 they used all over the world. I thought I read the other day where Douglas was kicking them out every 20 minutes. Now I can’t believe they were kicking them out that fast, but they made a lot of those. I never saw how many they made. Now the 47, they made 16,000 of those. I never saw about the 40, but the 40 was two or three years older than the 47. 16,000 sounds like a heck of a lot of airplanes, but every place you went the C-47 was there hauling something.

Headed Overseas

In Dec 1943 I knew I was going overseas so I sent my wife back to California and went back to Tallahassee, FL. Replacement Depot to await my orders. They shipped me to Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia. We arrived early Jan 1944. It was a base just before you went overseas. We were only there for 2 or 3 weeks to wait for shipment overseas. We loaded onto a troop ship at Hampton Roads, Virginia.

When we loaded, we didn’t know what was going on, but being officers, they made us get down in the hole with enlisted men who we didn’t even know. These infantrymen would come in with maybe 2 bags on their shoulders. The bunks were just about that far apart. You’re trying to tell them what to do, and they’re looking at you, like, who the hell do you think you are? So I didn’t like that part. Usually you’d have a Sergeant who would handle the men, but you were supposed to give orders. There’s no way you knew any more about it than they did ’cause you were new down there too.

The sleeping arrangements you can’t believe. People today your size could not get in one of those bunks. The bunks were only at the most 6 foot long, and they’re just about that much clearance between them. They were stacked about four high. We went over on that troop ship, and we were one of the first ships that went over to Europe. We went to Oran, North Africa, unaided; all by ourselves. The ship would go right, and it would turn, and go left all the time, every so many minutes or something. It would go in different degrees that keep the submarines from hitting us with torpedoes. We must have traveled twice as far as it was over there, zigzagging back and forth.

By that time in the latter part of Jan. 1944, we had taken North Africa in the war. North Africa was ours. From there they loaded us onto a narrow-gauge railroad to take all the 40 and eight (40 men and eight horses), and we went across North Africa from Oran over to some place around Algiers. It was supposed to be an airfield, but there were no airplanes there. It was just a field that they’d used during that part of the war. There we stayed in tents for a couple of weeks. They said that we’d get more flight training there, but they didn’t have any airplanes, so we didn’t get any flight training. After that they used C-47’s, the old workhorse twin engine Transport, and transported us up to Naples, Italy.

By that time, all I was worried about was it had been about 2 1/2 months since I’d flown. You get your flight pay as a second Lieutenant; I think it was $150. You got $75 if you flew 4 hours a month. I think maybe you only had to fly maybe four hours in three months. I don’t know about that. I don’t remember. But anyway, it was pretty near 3 months when I joined the 79th Fighter Group, and I told the squadron commander I’ve got to get 4 hours so I can get this flight pay. So he gave me an airplane to go out and just run around and accumulate 4 hours.

Part #6 Walter L Manning, 86th Fighter Squadron

Fighter Missions

My first combat mission was Feb 17, 1944. In that mission, I was in the second group, was going up to Anzio, where the invasion of Italy was. My best buddy was in the first mission. They took off at around 6:00 o’clock, and they were back like 8:30 or so. I was going to go to Anzio in the next bunch, usually 16 airplanes. When I got in my airplane, I asked the mechanic, I said, did all of them get back ’cause they was landed. He said no. There’s one missing, and it was my best buddy. He was shot down their first day up there. They were at 500 feet and went across the German lines, and they shot him down the first day.

When we got up there, the weather had cleared up a little bit. We’re supposed to just go over the troops to keep the Germans from coming in. We’re just going back and forth, back and forth. So we were always there. Wasn’t really doing that much, but just then 24 of them came down through us. We had to get rid of the belly tank, and it was a strange airplane, and the levers weren’t always in exactly the same place. By the time I really got to where I knew what was going on, they had gone home.

I don’t remember much about it. It happened so fast that you didn’t know what was going on, and my other buddy, they were on his tail shooting at him. We got back home okay. They were asking him how come he didn’t break right or left when they were yelling. There was a lot of noise on the air, and he didn’t quite know that there was somebody shooting at him. They put up a notice on the board that they needed a P-40 pilot to be a general’s aid. You had to be able to fly a P-40. He went and signed. He never flew another mission. He had all the war he wanted. So out of the four guys I went in with, we lost two on the first day.

Most of the things I did on missions were dive bombing on the bridges and a lot of strafing cars and trucks and railroads. North of Rome there was about a period there for 5 or 6 weeks, we were up there sometime 2 and 3 times a day shooting stuff on the roads. When Rome fell, they hadn’t had a railroad into Rome for about a month because we had torn up the track so much the trains couldn’t come in. So the people in Rome were short of food and stuff at the time.

We didn’t really go a long way like in England. We would go up along the coast of Italy and go out and go up to along the coast and then go in and do our bombing and strafing and then come back over the water and come back home. That way you didn’t have people shooting at you all the time. So the navigation part was really easy there, and then Vesuvius blew up while we were there. And so you had that cloud from Vesuvius to navigate by. You just looked to see where that cloud was and headed for home.

Thinking back about 16 missions, and most of them would have been Anzio missions in the P-40’s, and only a couple of them would have been involved in bombing. A lot of them were just showing our presence over Anzio to keep the Germans from being there. They would have liked 12 or 16 airplanes up there all day long. One squadron would come in and fly, and about the time you were supposed to go home with your gas getting low, they’d have another squadron come in. They just patrolled over the troops all the time. It probably gave the troops a better feeling, and then it also kept the Germans from coming in. So that was the first kind of mission I flew. When I got the P-47, it was mostly strafing and dive bombing. Once in a while we’d escort somebody, but not very often.

I never was in what you call dogfights. It’s just that we didn’t see that many airplanes. Once in a while you would see some, but in all the time I was flying, we only shot down one airplane. The squadron I was flying in probably had maybe 4 or 5 while I was there, but I was never on the missions where they shot one down. Our job was to lug bombs up someplace and try to blow up a bridge or railroad track or mostly strafing railroad tracks and things like that. We never went up very high, and there you had 8.50 calibers on that P-47 and the P-40 only had six. I don’t know how many rounds there were, but on the 47 you’d shoot 8 guns, and it seemed like you were throwing an awful lot of lead out there once. You had to shoot them all once. You couldn’t pick one or two of them. When you pulled the trigger, you shot all 8.

I’ll tell you a good story about the P-47. My flight leader was Edmund Lemmon, and he had four airplanes. He flew the one flight leader, and I had his element. That was his element leader. I flew 2 and his wingman had a bomb hang up and not come off the rack. In those days, if you had a bomb hung up, you had to bail out because they’d had people land with a bomb on, and then it exploded which it is not supposed to do. It’s supposed to fall off and go down the runway. It’s not supposed to explode. They had some explode, and you had to bail out if you had a bomb. This kid naturally didn’t want to bail out if he didn’t have to. Then to save the airport, he went in, took his wingtip, pushed it in under the other guy’s wing and got it in against that bomb and knocked the bomb off the shackle. He got a Silver Star for it. He was out of Louisiana. Edmund T Lemmon. Both pilots there had to stay pretty steady. He had kept inching in until he got that wingtip in there where they knocked that bomb off the wings.

Enemy aircraft were 109’s that day; either the 190, the Focke 190 or the 109. I never saw many airplanes. By ‘44, especially by the middle of ‘44, we pretty well controlled the skies. They were there, but not in the number that we were there. They built a lot of airplanes for the US compared to what we had in the beginning of our involvement in WWII . I mean they really turned out a lot of airplanes.

Part #7 Walter L Manning, 86th Fighter Squadron

Back in the USA

After my last mission, I spent a couple of weeks transporting P-47’s between Casablanca, Algiers, Tunis and Naples. Received movement orders 11 August 1944 for return to the US by water from overseas.

For the remainder of 1944 and 1945, I served as an instructor at Harding Field, Baton Rouge and Strother Field in Kansas. Most of this time we were flying P-47’s giving instruction in combat tactics, formation flying, night flying, air-to-air gunnery, and air-to-ground gunnery.

I received an Honorable Discharge Aug 29, 1945.

Looking Back Now

I don’t really think our training was adequate by the time we deployed to Europe. In fact, one of the problems we had was they had your name, and they’d have these squares, and the square would say ‘one-hour formation’ or ‘one-hour dive bombing’ or ‘one hour this’. In the class I went through, the instructor would go up there, and he’d say, oh, you needed aerial gunnery, but then he might send you out to fly in formation. They just recorded your hours for an air gunner. They didn’t follow what was missing. In the next class after ours, they sent pilots back through again because somebody complained that they weren’t doing all the training. In my class, I guess, we just thought we were getting by as long as we were flying. You weren’t worried about whether you were trained or not. Sometimes it was slipshod on the training.

I probably have some other stories that I could tell, but they might not be fit to tell. All I can say is I lost my buddy the first day, and I don’t know how come I was lucky. You didn’t have to be really good. You had to be kind of lucky.

I never flew again after the war except in a passenger plane, and it was years afterward. It seemed like the nose pointed up, and they just went up. We used to fight our way up a little bit at a time. It just amazed me that they could turn that nose up and take off. I’d just like to ride in a jet once that would go up to 30,000 feet, and just pull off the runway and go to 30,000. For us to get 30,000, I don’t know how long it would take. It did take you quite a while to work your way up to 30,000 feet. I don’t suppose they make over 500 feet a minute or something like that. Maybe not even that.

You know I remember going to an airplane before I learned how to fly, and the man that was with me was about 40 years old. He said, do you think you could ever fly one of them? And I looked, you know, they got a lot of different things on the dash. I couldn’t see how, but I didn’t really pay that much attention to a lot of those when I flew. There are certain things you paid attention to, and maybe you should have paid more attention.

I never thought that I was trained very well as a mechanic. I knew nothing about the motor part of it. My crew chief was T/Sgt Bates Shuping. He was a real good mechanic. He got the airplane ready, and he said in the morning if it was ready, or it wasn’t ready. They told you where you were going, you went out and you crawled up in it and took off and came back. You told him what you thought was wrong with it ’cause you always had to sign a piece of paper. Like you thought it was running rough or something you didn’t like about it, then he fixed that. Next day you walked out and got in it. So it was you really who wasn’t paying attention to the airplane. You just get in it and taking it off, and I’m ashamed to say that I’ve never walked around an airplane before our mission to see if everything was alright. Usually, we didn’t have time because there was one 15-minute alert. They would just holler go and you just run out there, and they drive you out and you jump in the airplane and take off in it. But I can look back, and it seems like there are things I should have done that I didn’t do, but nobody else was doing them either.

I said to my doctor awhile back, I’m 90 years old. He said there ought to be somewhere they could ‘can’ my genes or something. He said you had to have good genes just like you had and have a rabbit’s foot to get through the war. It wasn’t always the best pilots who got through the war.

Part # 8 Walter L Manning, 86th Fighter Squadron

Before and After the War

written by Walter’s First-Born Daughter, Julie Jackson:

Dad grew up in a small town along with 4 younger sisters. He attended a one-room country school through the 8th grade and completed high school in a nearby town. He loved sports, especially baseball, and after high school played a year of semipro baseball in Minnesota.

He enlisted in the Army 3 months after Pearl Harbor at the age of 20. He was placed in the Army Corp of Engineers, but within a short period he managed to move to the Air Corp where he learned to fly. He became a fighter pilot where he flew 106 missions in WWII. He was flying missions when I was born in June ‘44. He told me once that when he received word I had been born, he told them he was done flying missions. He flew his 106th mission on July 11, ’44.

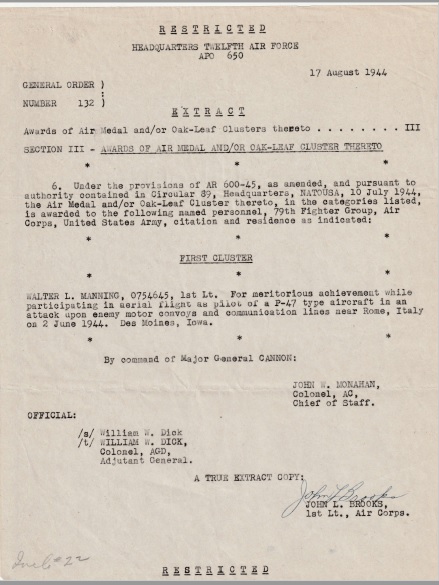

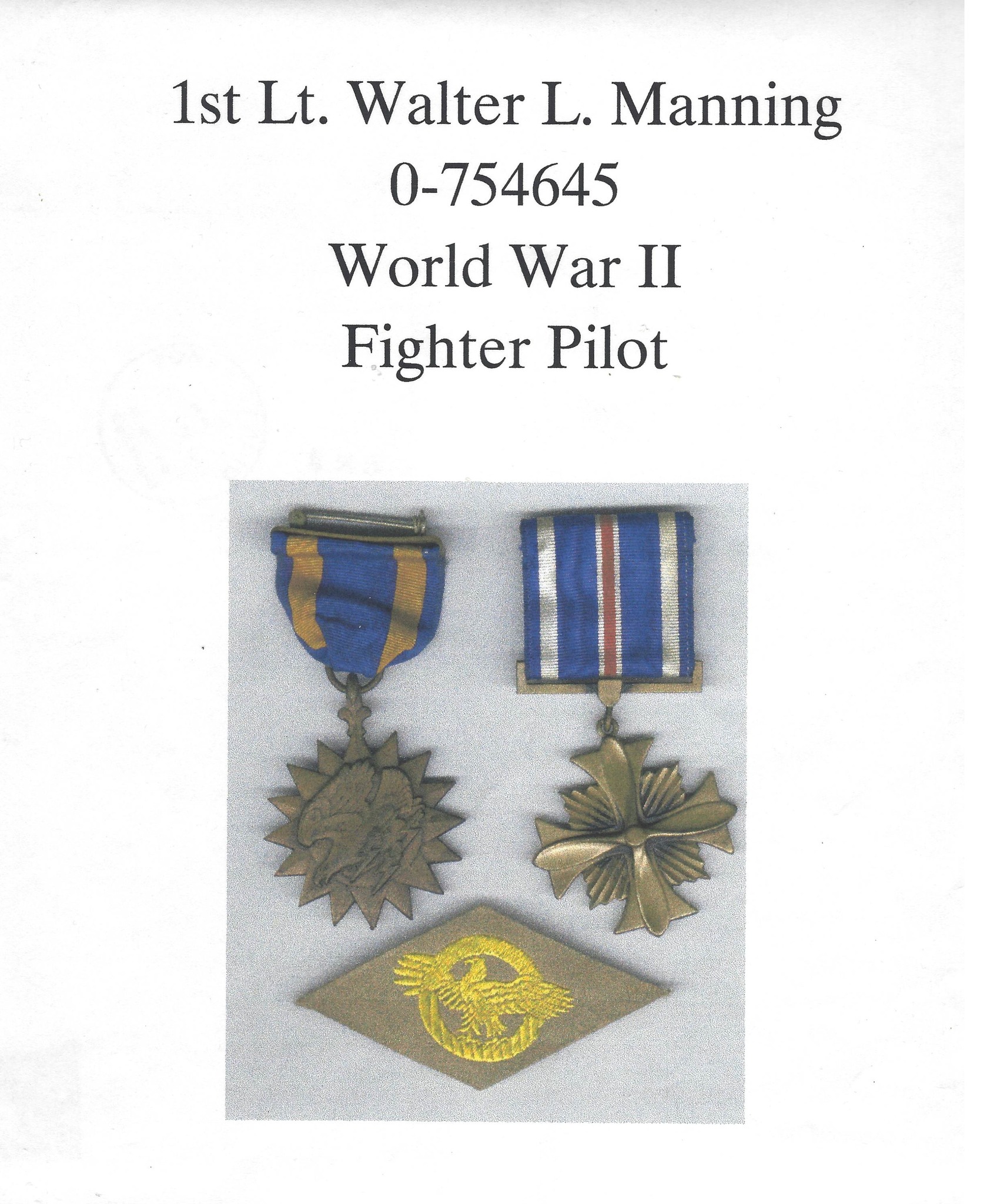

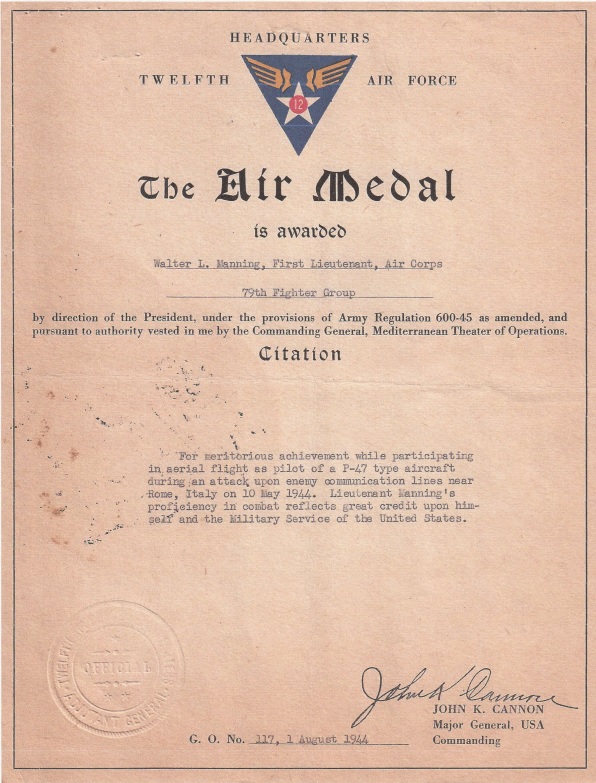

He was awarded the Air Medal on 10 July 1944 for meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight as pilot of a P-47 type aircraft in an attack upon enemy communication lines near Rome, Italy, on 10 May 1944.

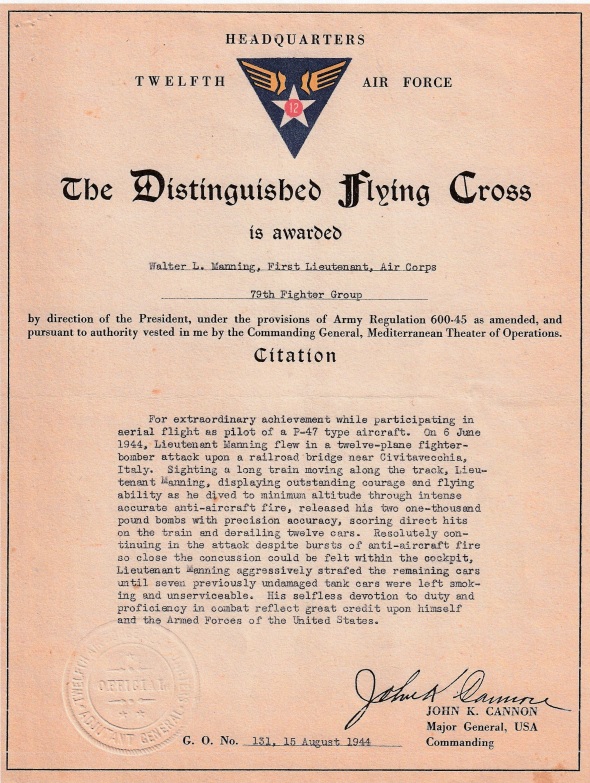

He was also awarded The Distinguished Flying Cross for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight as pilot of a P-47 type aircraft. On 6 June 1944, he flew in a 12-plane fighter-bomber attack upon a railroad bridge near Civitavecchia, Italy. Sighting a long train moving along the track, he dived to minimum altitude through intense accurate anti-aircraft fire, and released his 2 1000-pound bombs with precision accuracy, scoring direct hits on the train and derailing 12 cars. Resolutely continuing in the attack despite bursts of anti-aircraft fire so close the concussion could be felt within the cockpit, he aggressively strafed the remaining cars until 7 previously undamaged tank cars were left smoking and unserviceable.

He received a First Oak-Leaf Cluster on 10 July 1944 for meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight as pilot of a P-47 type aircraft in an attack upon enemy motor convoys and communication lines near Rome, Italy on 2 June 1944.

After being discharged from the military, my dad and mom moved back to Iowa. Upon returning to Iowa, my two brothers and sister were born. He was employed at Firestone Tire and Rubber Company for 39 years where he built tires early on and worked in the mold shop later in his career.

Dad was a “do it yourself” guy. He and Mom built our home themselves except for the basement and framing. He enjoyed his family, fishing, gardening and numerous other hobbies, such as making jewelry from rocks and creating stained glass art. He also coached both sons and their friends in Little League for several years.

Books were extremely important to him. My parents drove to the library on a weekly basis. He continued to expand his knowledge in many areas, purchasing his first computer after retirement and proceeding to learn to do some programming for his enjoyment and editing photos in Photoshop.

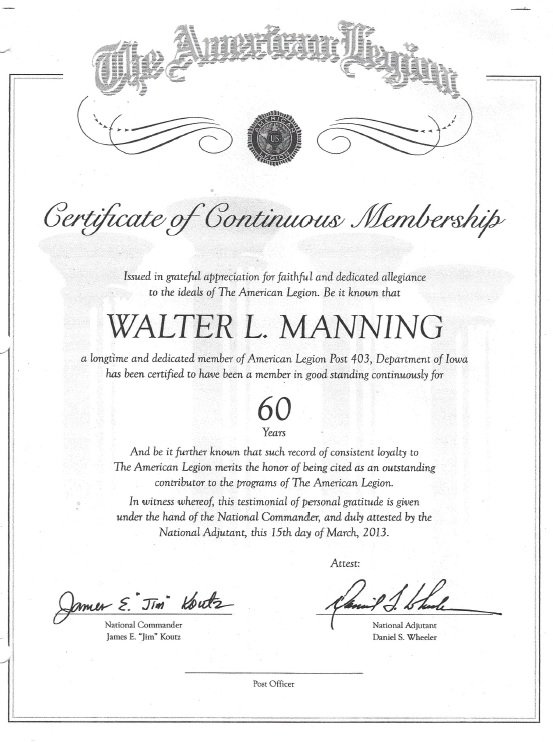

Dad rarely ever mentioned the war while we were growing up. However, after retiring he started attending reunions of WWII pilots around the country. He also compiled a detailed history of his service. In 2012 he was interviewed at the Iowa Gold Star Military Museum regarding his WWII service. The museum has compiled a library of interviews of men and women who served to preserve their stories for generations to come.