William C. Glasgow

A tribute to the life and legacy of pilot William C. Glasgow by his first cousin (once removed), Andrew Glasgow.

Part I

Capt. William C. Glasgow (1917-1945) Part I: Welcome to North Africa and the 79th!

I am going to make several posts about my 1st cousin (once removed), William Glasgow because he became an important part of my life 67 years after his death. He did not survive the war, and therefore I never met him. Although my father and William’s younger brother were very close friends, I knew almost nothing about William until a few years ago and after my father and all the Glasgow contemporaries had passed. But in 2012, while working on my family genealogy, I unexpectedly started down a path with William that would lead me to:

- find a maternal cousin of William’s who was a contemporary and who was intent on keeping his memory alive;

- find a man who was his roommate in 1945 and an eye witness to his death:

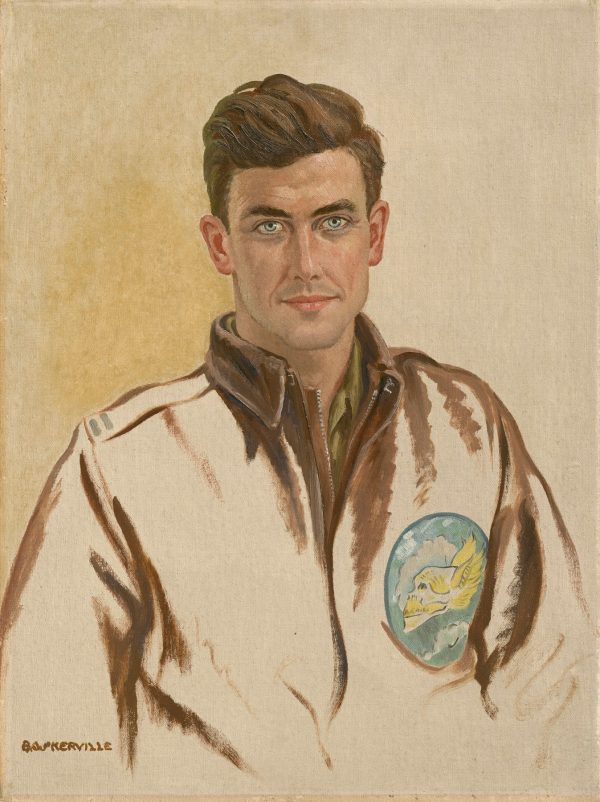

- obtain a digital copy of his portrait that has been on display in the Pentagon since 1945.

- make presentations about him and donate portraits to two air museums;

- speak with two authors who would write about him in recent books;

- make numerous presentations to church groups and genealogical groups.

William Clarkson Glasgow originally joined the Army in October, 1940, hoping to fulfill a lifelong dream to become a pilot. The Army, in its infinite wisdom, assigned him duty as a truck mechanic in an infantry division. When his one-year enlistment expired the following October, William was honorably discharged and went back to civilian life.

Then Pearl Harbor happened, and on January 20, 1941 William re-enlisted, but this time as an Aviation Cadet. He was sent to St. Petersburg FL for pilot training.

Upon completion of his training, Lt. Glasgow joined the 79th FG /65th FS in North Africa on 1/19/1943. At age 25, William was probably considered one of the “old men” of the group. He was also designated as Group B flight leader. I don’t know much detail about his life during this time, except for three missions which were not “routine”.

The first “event” occurred on April 23, 1943. Upon returning from a mission, William’s P-40 had a fatal mechanical failure. William was able to land the plane and walk away with only a chipped tooth. Don Woerpel gave me the attached photograph of the plane which appears in The 79th Fighter Group Over Tunisia, Sicily, and Italy in World War II on page 61.

The second “event” occurred during a mission that November in the skies over Italy. For his actions that day, William was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Here is the citation:

“William C Glasgow, 1st Lt. Niagara Falls, NY. For extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight as pilot of the P-40 type aircraft. On 7 November 1943, while leading his flight and strafing enemy motor convoys near Pescara, Italy, Lt. Glasgow’s aircraft was severely damaged when one wing struck a tree as he dived to a minimum altitude attack. Displaying great courage and determination, Lt. Glasgow continued his mission and led his flight in destroying one large motor truck and heavily damaged eight other motor vehicles. All p-40s returned safely to base. Engaging in more than eighty combat missions, Lt. Glasgow’s aggressive leadership and outstanding proficiency as a pilot reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of the United States.”

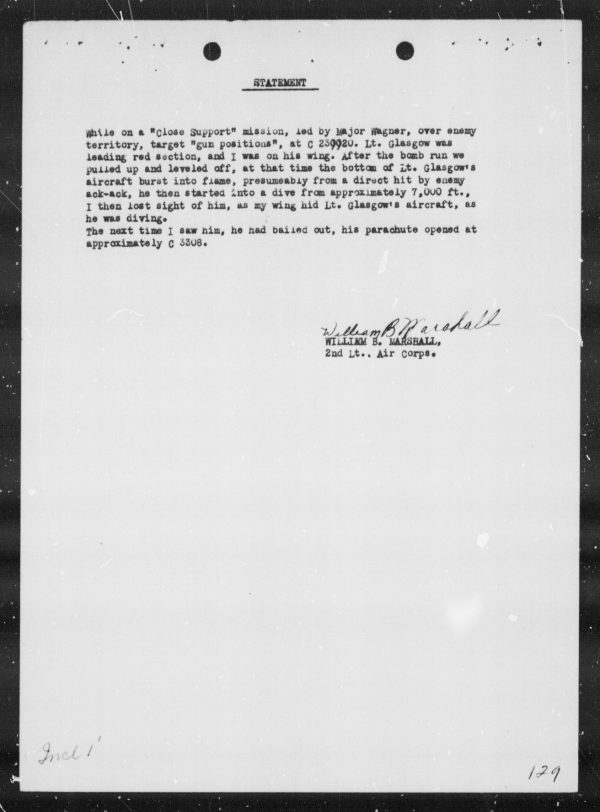

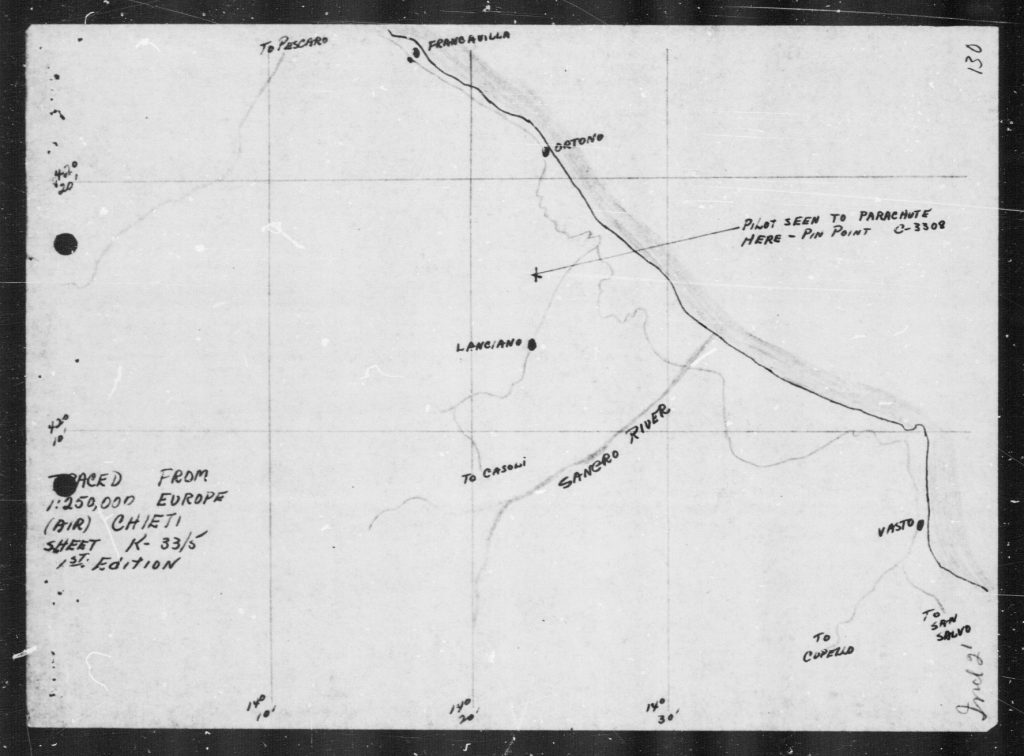

He flew 79 ground support missions without so much as a bullet hole in his P-40. On December 8 on his 80th (and presumably last before mission before rotation home) he was shot down by flak near Osogna, Italy. Lt. Charles Kehr of Westville NJ was also shot down on that same mission, but he did not survive. Despite being wounded, William managed to exit the P-40 and parachute safely to the ground. He was quickly captured by German troops.

Lt. Glasgow made his first (unsuccessful) escape attempt from the ambulance that was transporting him to a POW hospital. He successfully escaped his second night in the POW hospital by jumping out a 2nd story window. 13 days later, he was back at the 79th base bearing intelligence about German positions and equipment. Lt. Glasgow was decorated with the Silver Star and promoted to Captain. for his actions during this time period. The citation reads:

“William C Glasgow, 1st Lt., Niagara Falls, NY, exhibited unusual gallantry in action against the enemy in that, although injured by shrapnel from anti-aircraft shell which struck his aircraft in Dec. 1943, near Lanciano, Italy, and was captured by the enemy after he parachuted to the ground, he made two attempts to escape from his captors. On the second daring attempt he was successful in escaping from a German military hospital, and in face of great odd and in spite of a painful injury, he made his way back to Allied lines

He traveled for twelve days under the most trying circumstances, in the cold and rain, inadequately clothed, without food and sleep, and over some of the most difficult terrain in central Italy. It was only through exercising the utmost resourcefulness and an undying determination that he was successful. He disclosed the location of two large enemy gasoline dumps, and in addition brought back much general information of value to the Allied Forces. His courage, fortitude, and fearlessness is an inspiration to all members of the Armed Forces.”

Thanks once again to Don Woerpel’s book, we know more details about those twelve days as Don obtained a copy of William’s after-action report. My favorite part of William’s story is this section:

“For the next two days I traveled only at night, sleeping in barns and hen houses during daylight. On the third day, I found three isolated farm houses owned by three brothers who took me in for the next three days and nights. These Italians treated me swell. They fed me plenty of macaroni, brown bread and wine, and farmers came from all around to see me and try out their rusty English. There were also three single girls living in one of the houses, which made a good situation even better.”

After some recovery time in a hospital in Italy, he became the Acting Group Operations Officer at the 79th HQ. In April of 1994, William was sent back home to Niagara Falls for R&R and some PR work for the Army. Unbeknownst to him, it would be the end of his time with the 79th Fighter Group.

Part II

Capt. William C. Glasgow (1917-1945) Part II: You Can’t Go Back!

Back in the states, William visited the Curtis-Wright plant in Buffalo where all of the P-40’s his fighter group flew were manufactured. The P-40 was almost obsolete before WWII started. The main thing it had going for it was it was in production in 1941. Small design improvements were quickly made, and the P-40 formed the core of the US fighter force until mid-1943, when one-half of all US fighters were P-40s. By the time production ended in late 1944, 13,738 planes had been built in the Buffalo plant. It was the last production fighter Curtis-Wright ever built.

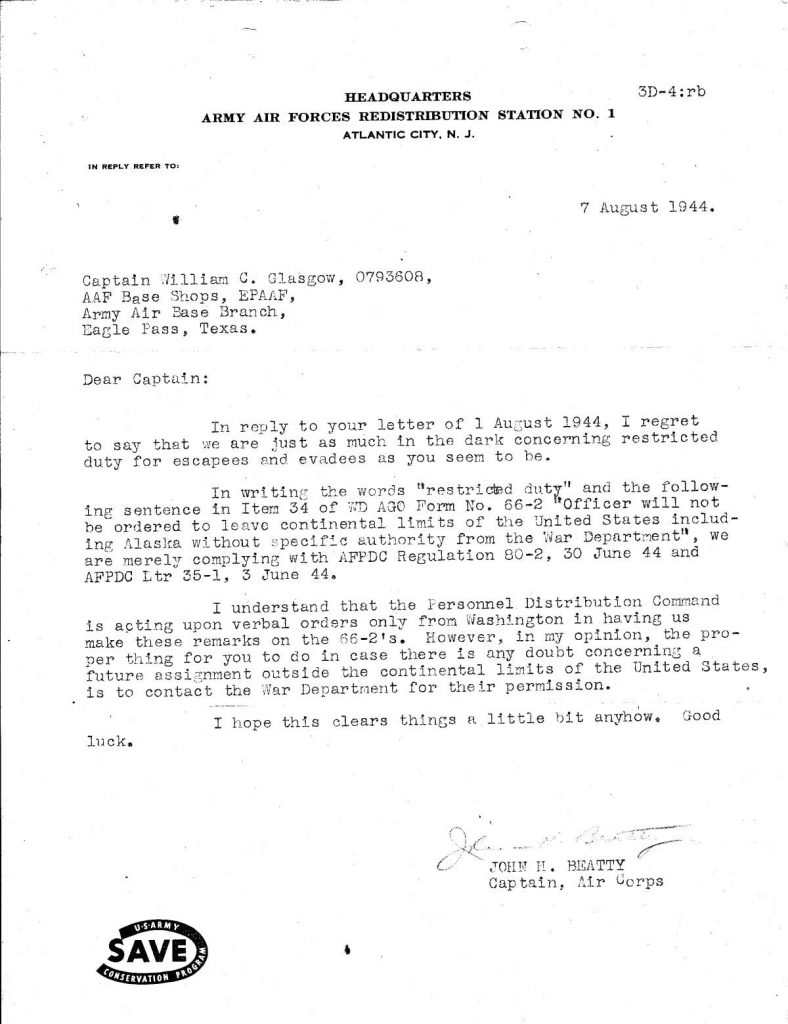

William made other visits such as to the Red Cross where he thanked them for the packages which made every soldier’s life a little better. After some time with his family, he made inquiries about returning to his unit in Italy. It was then that the he learned of a new military policy regarding “escapees and evades”: any soldier or flyer who had been a POW or had evaded capture behind enemy lines, was now prevented from leaving the continental United States. The military brass was concerned that any such soldier might be recaptured, and then tortured to reveal anything he know about the underground, resistance movements, or any civilians who had aided in his escape or evasion. William was evidently unaware of this policy, as was his commanding officer, as the attached letter shows.

William was therefore not allowed to return to the 79th, or to any active combat unit. Faced with this limitation, but still not having satisfied his love of flying, he opted for the next best opportunity: in early November, 1944 he transferred to the Fighter Test Pilot program at Wright Field in Dayton, OH.

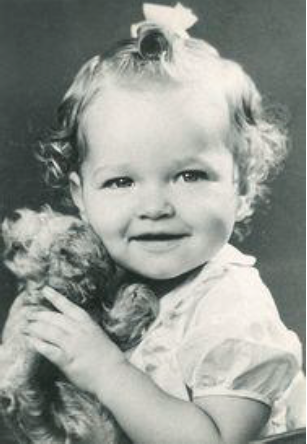

Notice the chipped tooth in this photo, which is from the crash on 4/23/1943.

——————————————-

There is a little known but related side story about America’s most famous pilots, Chuck Yeager. Yeager was also caught up in the escapee/evade web. March 5,1944 on his eighth mission flying P51’s out of England, Yeager was shot down over France on. With the help of the French Underground, he avoided capture and eventually made it to Spain on March 30. He was back in England by May 15. Yeager wanted and expected to return to combat, but the US policy on repatriated airmen prohibited him from returning to combat

However, Yeager was persistent AND he had connections that got him a personal meeting with Eisenhower on June 12,1944. By that time D-Day had happened and the French underground was now fighting openly alongside the Allies in France. As a result of these changing circumstances, Yeager convinced Eisenhower to make an exception and he returned to flying combat missions. Yeager was one of only two pilots to get such waiver during WWII.

After the war ended, the evader status came in handy as it allowed Yeager to choose his next assignment. He also joined the Flight Test Division at Wright Field in Dayton, initially working as a test pilot of repaired aircraft. Both Captain Yeager and Captain Glasgow served in this unit at Wright under Col. Albert Boyd, who became known as the “Father of Modern Flight Testing” and the “World’s #1 Test Pilot”. It was Col. Boyd who selected Yeager to fly the X-1 in the famous sound barrier breaking flight in October 1947. Boyd’s contributions to aviation progress are in hundreds of design details of military aircraft flying today, as well as in the achievements of a whole generation of test pilots and the first generation of space pilots. In the decade 1947-1957 Boyd’s opinion that he gave after flying a new airplane generated so much respect that the Air Force never bought a single type of airplane which he had not personally approved. Boyd retired with the rank of Maj. General in 1957 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Part III

Capt. William C. Glasgow (1917-1945) Part III: The Air Force Art Collection

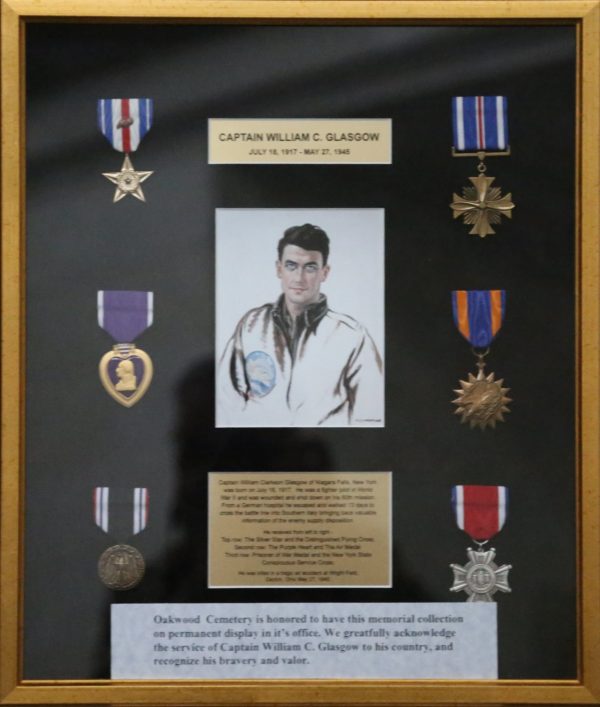

This portrait of Capt. William C. Glasgow (1917-1945) has been on display in the Pentagon since the end of WWII, as part of the Air Force Art Collection.

As part of the public relations effort in WWII, the Army Air Force engaged the services of noted portrait painter to paint a collection of 65 officers and enlisted men. A description of the collection reads:

“The actions and deeds of Air Force men and women are recorded in paintings by eminent American artists in a way words alone could never tell. These paintings are both historical and educational and expose the military and the public to the role and diverse capabilities of the United States Air Force.”

The Army was incredibly fortunate to be able to enlist the artistic services of Col. Charles Baskerville, Jr. (1896-1994). Baskerville was not only a Silver Star decorated WWI veteran, but also the most noted portrait artist in America at that time. At age 46, he re-enlisted during WWII hoping to again serve his county again in some capacity.

Charles Baskerville, Jr., was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, but moved with his family to New York as a child when his father (and namesake) was hired as a chemistry professor at the College of the City of New York. After high school, Baskerville enrolled at Cornell University in hopes of becoming an architect. There, in addition to his major studies, he gained practical experience as the art director of both the university’s yearbook and its satire magazine, The Cornell University Widow. Though his focus eventually shifted to painting, Baskerville would routinely turn to book and magazine illustration as an artistic outlet throughout his career.

Baskerville’s studies were interrupted in 1917 when the United States entered World War I. In July of 1918, the young lieutenant was injured in combat, resulting in a brief hospital stay. During his convalescence, Baskerville passed the time by making sketches that were later published in Scribner’s Magazine. These drawings included images of his comrades at rest, injured troops, and scenes of soldiers in the midst of the very conflict that had resulted in his own injury, according to the magazine. Twelve days after his initial injury, Baskerville was exposed to gas in a separate skirmish, which left him shell shocked and incapacitated, resulting in an honorable discharge that earned him a Silver Star for gallantry in action.

After his graduation from Cornell in 1919, Baskerville pursued work as a commercial artist and portrait painter in New York. As a contributor to The New Yorker, he wrote and illustrated a popular nightclub column under the pseudonym, “Top Hat,” resulting in widespread recognition throughout the city and increased portrait commissions. As a portraitist, Baskerville was sought out by an elite clientele that included an impressive roster of influential citizens, from business executives and socialites to actresses and foreign leaders. Those who sat for him included Jawaharlal Nehru, Bernard Baruch, William S. Paley, the Duchess of Windsor, Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, Richard Rodgers, Helen Hayes and the King of Nepal.

Baskerville was also extremely prolific as a muralist and a painter of still lifes, such as Yellow Apple. His mural work surely benefitted from the connections he made as a portraitist, because the commissions were often located in the kinds of spaces that his patrons—especially wealthy women and military officials—frequented. For instance, Baskerville was commissioned to paint the murals in the first-class lounge of the ocean liner SS America, the conference room used by the Joint Committee on Military Affairs at the US Capitol in Washington, DC, and the pool house at the Long Island estate of businessman and philanthropist Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney.

Military service in World War II took Lieutenant Colonel Baskerville abroad as the official portrait painter of the United States Air Force. In that position, he created over sixty portraits of officers and soldiers that were exhibited widely during and after the war, and are now on permanent display at the Pentagon. Regarding his WWII portraits, Baskerville was quoted as saying, “Of all the work I have done in my life, those portraits are what I am proudest of.”

Mr. Baskerville had a dozen one-man shows in New York, and his work was exhibited at the in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Some of the other persons included in the Baskerville collection include Lt. Gen. James H. (Jimmy) Doolittle, Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault, Lt.. General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, Maj. Richard Bong, Capt. Don Gentile, For more about the Air Force Art Collection:

https://www.afapo.hq.af.mil/…/Artists/artistsdetail.cfm…

Part IV

Capt. William C. Glasgow (1917-1945) Part IV: US War Bond Rally May 27,1945

WWII cost the US $300 Billion dollars. In order to pay for the war, Defense bonds were introduced in May, 1941, and later renamed War Bonds after Pearl Harbor. Bonds were available in denominations from $.10 to $1000, so even school children participated in the fundraising. There was a massive advertising campaign to sell bonds, which involved many Hollywood stars and famous entertainers. Newspapers and radio stations donated advertising space. There were eight major bond drives between 1942 and 1945, each was targeted to raise $9B to $15B. In fact, 85 million Americans (out of 131M) participated and the bonds raised $185.7B.

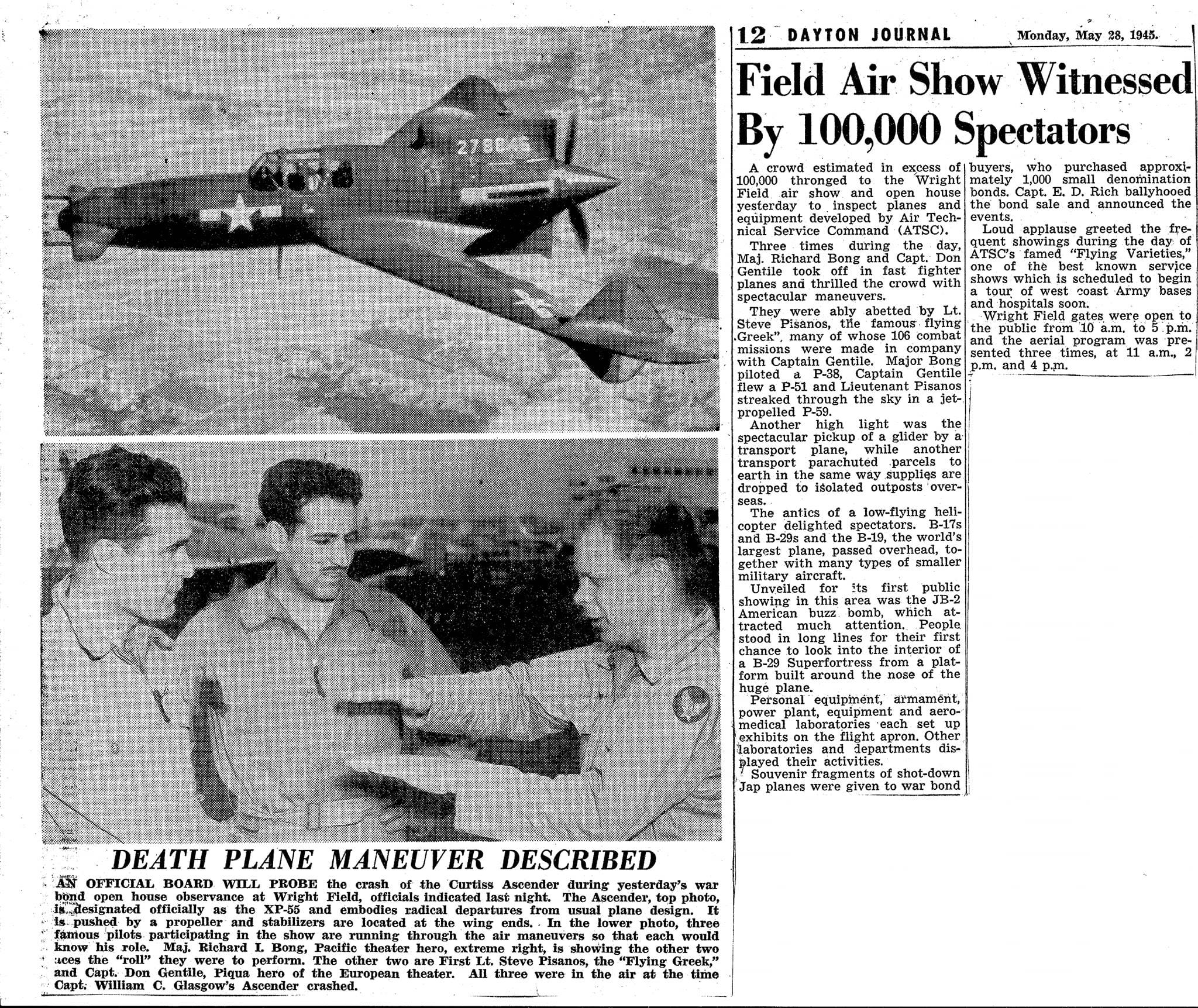

The 7th War Bond Drive commenced on May 14, 1945. One of the key events of that drive was an air show to be held at Wright Field in Dayton OH. Both Fighter Test and Bomber Test squadrons stationed at Wright were designated to fly in the show on May 27. Wright had a tremendous collection of planes, both Allied and enemy planes, as well as experimental models that were in development. Each pilot was allowed to select the plane he wanted to fly. Capt. William Glasgow chose to fly the Curtis-Wright XP-55 experimental fighter. Some of the other pilots and the planes they flew that day:

- Maj Dick Bong, 40 kills, CMH, in P-38 (Still the leading Ace in US History)

- Capt. Don Gentile, 20 kills, in P-51

- Lt. Steve Pisanos, 10 kills, P-59 (early jet)

- Capt. Glen Edwards, B-24 Bomber ((Edwards Air Force Base honoree)

In 2013, I managed to meet retired Col. Kenneth Chilstrom. In May 1945, Capt. Chilstrom was the Ops Officer for the Fighter Test group. Ken, William, and Glenn Edwards were also roommates.

Ken did not know why William chose to fly the XP-55, but we speculated there were a couple of possible reasons:

- The XP-55 was an exotic looking plan with the propeller in the rear, which would make it interesting for the air show crowds;

- William had the 2nd most hours of any pilot in the XP-55 testing;

- Loyalty: the XP-55 was made by Curtis-Wright, the same company that had made all of the 79th’s P-40’s;

- All the P-40’s were made in Buffalo, near William’s hometown of Niagara Falls;

- Curtis Wright had shut down product of the P-40 in Nov. 1944, so there had been layoffs in Buffalo;

- Success of the XP-55 test program might mean new jobs coming back to Buffalo.

There were three air shows that day, and it is estimated the attendance was as between as 50,000 to 100,000 at each show. Before the show, it was ordered that there were to be NO ACROBATICS. During the first show, the pilots overflew the area in front of the grandstands, but did not execute any maneuvers as per the orders. Upon completion of the first show, the pilots approached Capt. Chilstrom and indicated their displeasure with the restrictions. All the pilots were combat veterans who were used to extreme flying conditions, and they thought the simply fly by was boring. Wanting to give the crowd more of a show, the lobbied Capt. Chilstrom for permission to do a victory/barrel roll. This was considered a simple and safe maneuver that pilots executed at the end of every successful mission.

Wisely, Capt. Chilstrom escalated the request to Col. Albert Boyd, and then Col. Boyd escalated the request the commanding officer, Gen. Ben Chidlaw, who approved the change. The second show proceeded with the barrel rolls and no incidents. However, during the third show, Capt. Glasgow lost control of the XP-55 upon completion of the roll. His attempts to stabilize the plane failed when the XP-55 apparently stall, and the plane hit a fence at the end of the runway, cartwheeled, and disintegrated during the crash. William was killed instantly. Chilstrom, Bong, and Gentile were all part of the honor guard that escorted William’s body back to Niagara Falls for the funeral.

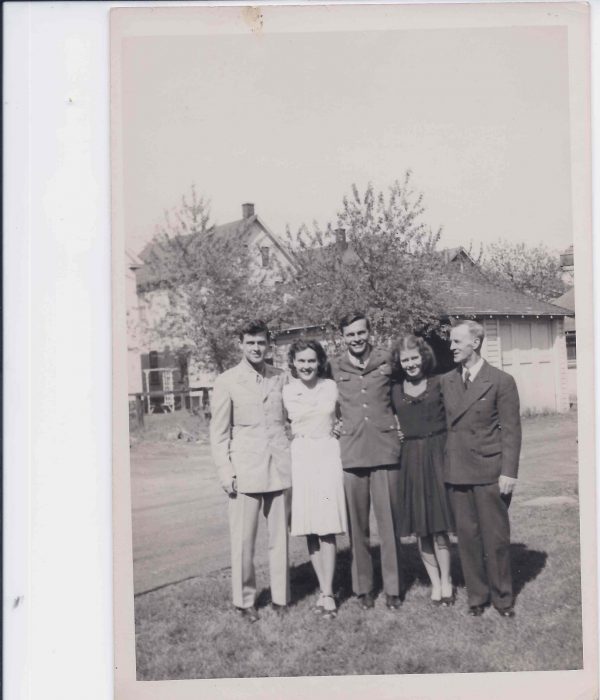

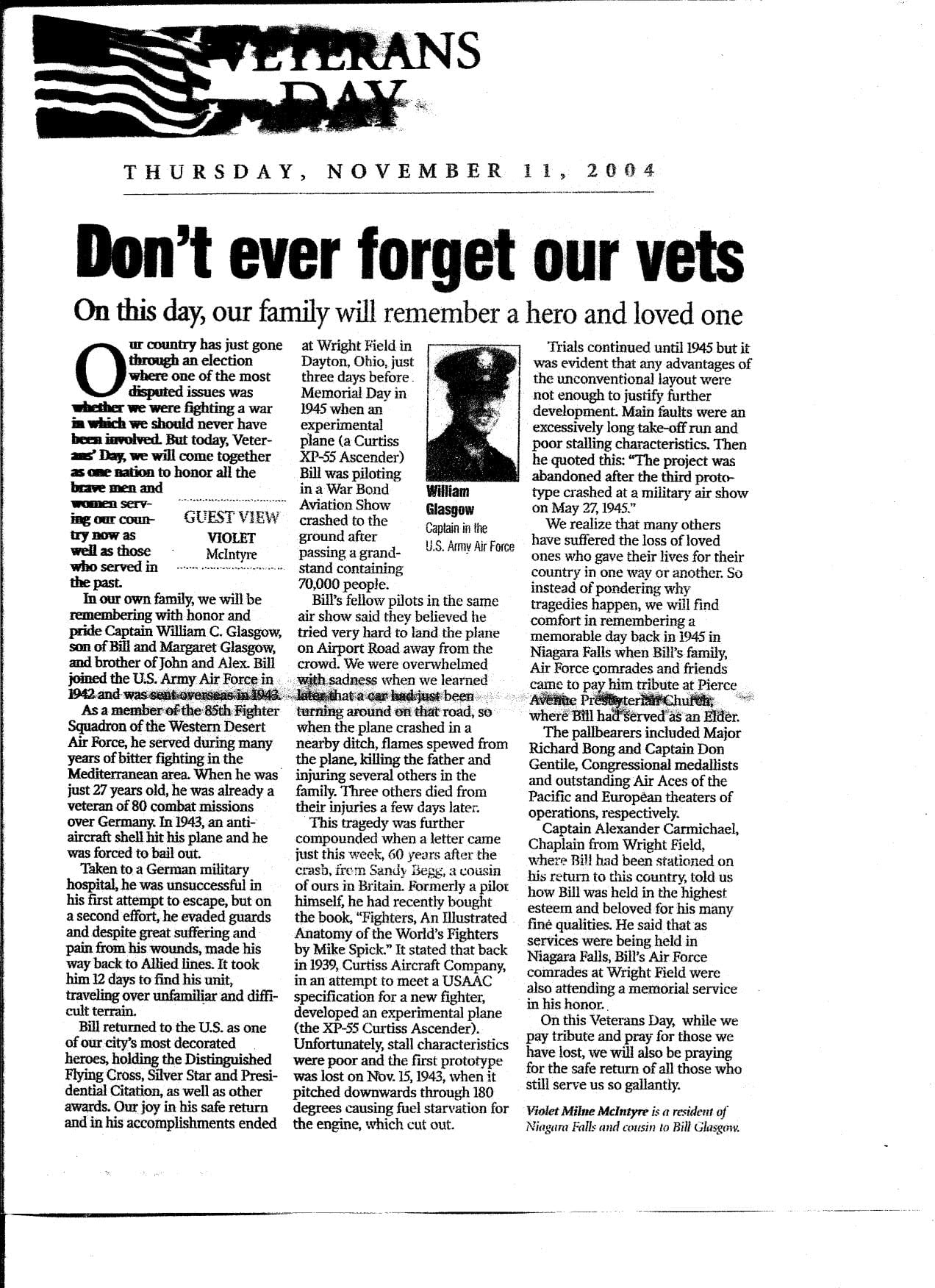

As mentioned earlier, I never met William as I was born ten years after his death. Before I came along, a maternal cousin named Violet McIntire was the keeper of Bill’s legacy. Violet was six years younger than William, but knew him well through family connections and church. We found each other by a quirk of fate, and she added a personal dimension to his life that was missing. Violet describes William as q humble, kind person with a wonderful smile and engaging personality. She told me he was the kind of person who always made you feel special when you were with him. Her Memorial Day tribute to him is attached, as is a photo with him from around 1944.

The XP-55 never made it into production. Jet fighters were already on the scene and the Curtis Wright designed plane had numerous performance issues. There is one surviving XP-55 on display at the Air Zoo museum in Kalamazoo, MI. Captain Glasgow was buried in Niagara Falls and there his portrait and career are part of the display at the Niagara Aerospace Museum. Kenneth Keisel also included a few pages on William in his book, Wright Field.

Bong, Gentile, and Edwards would all die in plane crashes between 1945 and 1951. Pisanos had an incredible career that started with the RAF in 1940, and included time with the French resistance after he was forced to land to France in March 1944 due to mechanical problems. Pisanos stayed in the Air Force until 1974, and only passed recently in 2016. In the book, The Flying Greek, he tells his own life story.

Ken Chilstrom went on the be the lead test pilot for the first swept wing jet fighter, the Sabre XP-86. He served in various other key roles in the development of new aircraft. Ken flew 147 different airplanes in his career with the Air Force before retiring in 1950 to work for GE, Boeing, and other aircraft companies. Ken is one of the nicest people I have ever met, and he became a family friend. When I first contacted him, he immediately invited me to visit him in Washington. He took my wife and I as guests to a luncheon of retired military pilots. One of the people I met that day, a retired general, helped me secure a digital scan of William’s portrait from the Pentagon, which allowed us to reproduce the painting and donate it to two air museums. As of this writing, Ken still lives outside Washington DC. He will turn 100 April 20, 2021.

Sole Survivor of the Dayton Airshow Crash

Nina Hampton, now 66, only survivor of 1945 Dayton Air Show crash.

Nina Hampton, a 66-year-old Marysville mother and grandmother, is the only survivor of the crash of a 1945 air show crash that killed five people, including her parents and older sister.

Nina Lee Roehm is shown as a toddler. Today, the 66-year-old Marysville mother and grandmother talks about being the lone survivor of the May 27, 1945, crash at an air show crash at Wright Field that killed five people, including her parents and sister.

By Mary McCarty – Staff Writer

Article is from 1999

Nina Roehm Hampton’s first outing in the world very well could have turned out to be her last.

She was only five weeks old on May 27, 1945, when her parents, Wesley and Susan Roehm, took the family out to Wright Field for an air show and war loan rally that drew 70,000 spectators.

Around 4 p.m., in the show’s closing hour, an experimental plane crashed near the Roehms’ car, spilling burning oil fuel over the vehicle. “Human torches,” a local newspaper headline blared.

In the end, Nina was the only one who survived the fiery crash that killed the pilot and four people on the ground — the only civilian deaths in Dayton air show history. It was a tragedy that forever changed air show safety in the United States — and forever changed the lives of three families.

Little Nina Lee owed her life to the quick thinking of close family friend Kathleen Eyre. According to family accounts, the 22-year-old Eyre tossed the newborn out of the car window before she too became engulfed in flames. Only Nina’s hands were burned.

Jack Darst of Beavercreek, then a high school student, watched the crash in horror.

“It was a low flyover from the west to the east, and the pilot did a moderate dive and high-speed pull up,” Darst recalled. “There weren’t any wild gyrations; it just didn’t climb. The plane skidded through a fence, and hit close to the Airway Road perimeter. The fire trucks couldn’t get through the fence to get to the scene. It was very chaotic.”

Nina Roehm Hampton, now 66, lives in Marysville, Ohio. She talked to the Dayton Daily News about her life and of the day it almost ended.

Hampton said her father, an engineer for a Dayton tool-and-die company, spent the day at the air show and had excitedly returned home to bring the rest of the family back with him, including Nina in her first public outing. The car had just gone through the ticket booth and pulled up along Airway Road when the plane burst into flames.

The pilot, World War II flying ace Capt. William Glasgow, was killed instantly. Wesley Roehm, 23, died at the hospital a short time later. Eyre died the next day and Nina’s sister, 20-month-old Donna Irene, died two days later.

Susan Roehm lived two more weeks, long enough to express her wishes that her husband’s parents, Grace and Vern Roehm, raise her surviving daughter, Nina.

“They didn’t tell her at first that my father and sister had died,” Hampton said. “She fought and fought, but after she found out the news, she lost her fight.”

It is an almost unthinkable tragedy — one that continues to reverberate in the Roehm, Eyre and Glasgow families more than 66 years later. Yet it’s also a powerful story of compassion and the staying power of family.

Hampton has been happily married for 47 years to her husband Tom, is the mother of two married sons and the grandmother of five. She shows a surprising lack of bitterness about the accident that claimed the lives of her family. She still has burn scars on her hands and as a child she endured several skin graft surgeries, but she carries no psychological scars. “I’ve had a wonderful life,” said Hampton. “I was raised by loving grandparents. The more I live, the more I realize God’s blessings. Because I lived, I have a responsibility to be a blessing to others.”

John Culdahy, president of the Virginia-based International Council of Air Shows, said the air show industry came under close scrutiny after the Dayton tragedy. “As a result of that accident, there was a close cooperative effort that developed a comprehensive set of air show regulations and rules that have done quite well at protecting spectator safety,” Culdahy said. Among the improvements: greater distances between spectators and aircraft, stringent qualifications for pilots and a prohibition against aerobatics while plane pointed at audience.

Since the new rules were adopted in 1952, not a single spectator has been killed at a North American air show. Air races, he noted, operate under a different set of flying rules. (Eleven people died Sept. 16 at an air race in Reno, Nev.)

None of the survivors has ever blamed the pilot. Glasgow’s mother, Margaret, sent baby clothes for Nina. Hampton, in fact, remembers visiting the Glasgow family in their hometown of Niagara Falls, N.Y. “How hard it must have been, to get him back safely from the war and then to lose him like that,” she said.

Glasgow’s cousin, Violet McIntyre, worshipped the war hero who had defied the odds by making it home after flying more than 80 combat missions over Germany.

“He was always a gentleman, and the ladies loved him, young and old,” McIntyre recalled. “If you met him for the first time, he could make you feel that you were the most important person in his life.”

The church was filled to capacity at Glasgow’s memorial service in Niagara Falls, N.Y. Pallbearers included fellow aces Capt. Don S. Gentile, and Major Richard I. Bong, Ace Pilot, who performed at the Wright Field air show alongside Glasgow and tipped their wings in tribute after he crashed.

Glasgow’s family now believes the experimental aircraft, the Curtiss-Wright XP-55 Ascender, should never have been permitted to fly in an air show. Because of its pusher design, it was known as the “Ass-ender” and only a few prototypes were ever produced The first crashed and further test runs revealed the plane’s excessively long takeoff run and poor stalling characteristics. “It never should have been used,” McIntyre lamented. “It was just a tragic thing; Bill got through the war only to die in his own country.”

Susan Roehm’s younger sister, Jane Davidson of Centerville, was only 13 when she lost her adored older sister, a star student in high school. “My mother and Dad spent a lot of time at the hospital in Dayton, and it was constant turmoil in our lives,” she said.

Yet she remembers many kindnesses, from neighbors bringing a parade of casserole dishes to the rationing board allowing the family to get more gasoline so they could make the trips to Dayton. “It was a summer you always remember,” Davidson said.

Beverly Dodds of Leesburg said her in-laws, Mildred and Ed Eyre, were never the same after the death of their daughter: “Kathleen was working as a secretary in Dayton. She was a little farm girl having her adventures in the city. She had been engaged to be married, and her fiance was killed in an airplane in the service.”

A U.S. District Court ultimately awarded $70,000 in damages for all five of the civilian victims, including $7,000 for Nina.

Because she had never known her parents or her sister, Hampton said, “It was never painful for me.” Her grandparents always told her the truth about the crash and didn’t shy away from telling childhood stories about her father. Hers was an idyllic childhood packed with music lessons, Sunday school, Farm Bureau Camps, and annual Fayette County Fairs.

Her grandparents made sure that she often visited her mother’s family and celebrated Christmas with them. “We are people who appreciate the value of family and getting together,” Hampton said.

She realizes now that her emotional resilience was the result of “being doted on by both sides of the family. I had everything a child could want in the way of love and support.”

When Hampton was a young mother, her grandmother lovingly compiled a scrapbook filled with photos of her family. “I will miss the photos of your Mother and Father but want you to have them,” Grace Roehm wrote. “They were a wonderful, happy young couple with great plans for the future. Little Donna with big brown eyes and dark hair like her Father’s was a beautiful child.”

“I didn’t dwell a lot on my parents being killed in an air show,” she said. “I was more focused on getting to my 4-H meeting.”

A woman of deep faith, Hampton believes she will meet her family for the first time in heaven. “I think that would be exciting,” she said. “I’ve got angels watching over me.”

To contact this reporter call (937) 225-2209 or email mmccarty@DaytonDaily News.com.